About Hilary Miller

Posts by Hilary Miller:

Claudia is a Brazilian student who scored super-well on the TOEFL (113 overall) the first time she took it. Despite a busy job and family life (she’s a wife and mother of three sons), Claudia managed to consistently work on her English with spectacular results. So how did she do it? Here’s a Q & A with Claudia.

What was your overall approach to preparing for TOEFL?

When students are preparing for the TOEFL, it is important that they immerse themselves as much as possible in the English language. Listen to American audiobooks, podcasts, and YouTube channels, watch American movies and TV shows, and even have their GPS talk to them in English (I learned a lot about directions in English with the Google Maps app). Also, they should try to speak with a native speaker at least half an hour every day.

Any more specifics for listening?

I am hooked on audiobooks. I believe this is the easiest and most effective way to learn new words, improve pronunciation, and get familiar with the rhythm of the language. I like to run, and I used to run listening to audiobooks in English instead of music. I listened to all the books by the young adult writer, Stephanie Meyers (Twilight, Dusk, Dawn, The Chemist, etc.), because her stories are captivating, and the English is easy to understand. I also listened to the last audiobook by Hillary Clinton, What Happened, because it is read by her and her rhythm and intonation are perfect.

How about podcasts and channels?

I would recommend subscribing to many English podcasts (I love All Ears English!) and YouTube channels such as Gabby Wallace – Go Natural English, Rachel’s English, SmallAdvantages, Amigo Gringo, and Ask Jackie. The last three ones are aimed at Brazilian learners.

Hilary’s Note:

Because preference in podcasts and channels is such an individual thing, here are some other recommendations from English learning websites. Keep experimenting until you find the perfect ones for you, and then try to listen consistently.

11 English Podcasts Every English Learner Should Listen To

12 Native English Podcasts for Learning English

Top Five Podcasts to Help You Learn English

10 Awesome Channels to Learn English on YouTube

7 Great YouTube Channels for English Learners

11 Of The Best YouTube Channels For Learning English

And, if you’re an advanced learner, consider Great Courses Plus, which Claudia discovered thanks to this blog 🙂

And what about TV and movies?

It is very helpful to watch American TV shows. First, I watched them without subtitles to try to understand as much as possible. Later, I watched them again, but this time with subtitles to make sure that I understood every single line. I used to write every new word or expression that I didn’t know in a notepad. My favorite TV show is The Good Place, while I think just about any American movie is useful.

Anything you’d recommend for translating?

My favorite online dictionary is Linguee

How about speaking practice?

For speaking practice, I like the app called Cambly. The teachers are not as prepared as the ones on italki, but I had the chance to talk every day with Americans for a very low price. Although you get what you pay for, I believe that it is very important to speak English with a native speaker every day when you are preparing for the test. On the other hand, the most prepared teachers for the TOEFL are on italki. So, students should invest some money in having classes with these teachers as well.

Hilary’s Note:

Italki is a Chinese-based company; Verbling, an American-based company, also employs more selectively hired professional teachers. Choose your teachers carefully if you are preparing for TOEFL Speaking. Although teachers may say that they’re trained to teach TOEFL and most can do a reasonably good job preparing you up to a certain point, to attain a really high score, you may need to find a teacher with more direct knowledge of the test and how it’s scored.

So let’s move on to reading. What helped with that?

I think students should read lots of academic texts. I like to read newspapers and magazines, but for the TOEFL test, I don’t think it is worth wasting time with them, because the style and the vocabulary are very different.

You scored 28 in Writing. How did you study for that section?

For the writing part, students should try to write as many essays as they can. However, before writing, they must be familiar with the essay structure and the topics used in the TOEFL, because the essay subjects tend to concentrate on certain areas, such as children, university life, hobbies. A good source of ideas is the following book:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1W8ndIzhOUIsfO6OOlEXOHhDl9jxzYdNd/view?usp=sharing

The essays in that book are not masterpieces, but they are realistic essays done by students just like us. These works are helpful to teach us how to keep an essay simple but effective. In addition, there are so many essays in that book that after reading 10 or 15 of them, you wind up creating your own method of writing a simple essay.

Hilary’s Note:

I agree with Claudia that the best way to practice is to write essays. The book she recommends contains some good essays, but I would not exactly recommend them as models to imitate. Please read my article about the TOEFL independent essay for more of my advice about the writing section.

Any other advice you can give?

One last piece of advice is not really for students, but for parents who want their children to master a foreign language. Although it is important to study English in their own counties, it is essential to expose them to an English environment at an early age. My personal history provides a compelling example of this. When I was fifteen years old, I went to the U.S. as an exchange student for three months. Although it was a short period, it made a huge difference to my English skills. I believe that, at a young age, our brain can better learn the rhythm of a foreign language, just like learning how to ride a bike.

Twenty-five years later, I went back to the U.S. with my husband and our three sons. My husband had a student visa, and our children were able to go to school for three months in San Diego. This short period was amazing for my boys’ English (at 13, 11 and 9 years old), but it wasn’t so effective for my husband’s English. I am saying this not to discourage anyone from learning English as an adult, but to encourage parents to send their teenagers to study and live abroad even for a short period of time.

You mentioned living in the U.S. as an adult. Did you work on your English there?

Yes! There is also one more thing that should help your students who already live in the U.S. Why don’t they volunteer to work at the local church or library? When I was in San Diego, I volunteered at the local church. It gave me the opportunity to speak with many different people in a welcoming, friendly environment. They even taught me how to answer the phone and how to give directions.

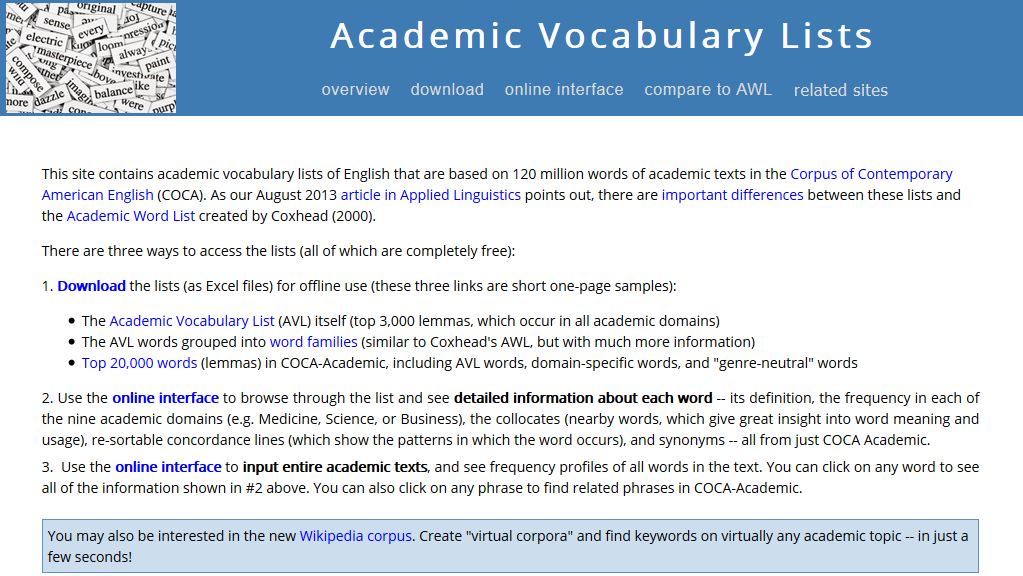

One of my more popular articles discusses two useful word lists, the Academic Word List (AWL) and the Fry Word List. Recently, another academic word list, the Academic Vocabulary List (AVL), has been becoming more popular with English learners and teachers.

The authors of the Academic Vocabulary List, Dee Gardner and Mark Davies, point out that, “Academic vocabulary knowledge is recognized as an indispensable component of academic reading abilities” and that “control of academic vocabulary, or the lack thereof, may be the single most important discriminator in the ‘gate-keeping’ tests of education.”

More simply put, you need to know lots of words to speak and write good English, and to pass tests such as the GMAT, GRE, and TOEFL. How many words? The average American high school student knows 75,000. They will be your colleagues if you plan on attending a U.S. college or graduate school. According to Gardner and Davies, the academic achievement gap between non-native English speakers and their peers is strongly associated with a lack of academic vocabulary.

The Academic Vocabulary List vs. the Academic Word List

Gardner and Davies have some objections to the Academic Word List (AWL) that I have recommended many times to my students.

First, the AVL is newer (2011) and based on a computer search of many more words (120 million words in 13,000 academic texts published in the U.S.). In contrast, the AWL is based on a mere 3.5 million words mainly published in New Zealand from the early 1960s to the late 1990s.

Second, the AVL uses a much different system than the AWL for grouping vocabulary words together in “word families” … one that the authors claim is better for English language learners.

Basically, the Academic Word List groups a variety of related words around single stem (headword). For example, the stem react includes reaction, reactions, reacted, reacts, reacting, reactive, reactionary, reactionaries, reactivate, reactivation, reactor, and reactors. Although these words are related, they may not share the same core meaning. In addition, the AWL does not distinguish their part of speech or how frequently each one is used. For example, among the singular nouns in this family, reaction is much more common than reactivation, reactionary, or reactor, but the AWL does not give you this information.

In contrast, the Academic Vocabulary List groups words by lemmas. Lemmas are words with a common stem (headword), related by inflection (such as -s, -ed, and -ing), and coming from the same part of speech. So, for example, the AVL would group the words apply, applies, applied, and applying. Because the AVL groups lemmas by parts of speech and then lists them in order of frequency, it is easier to identify which words are more important to learn. For instance, the noun effect is much more commonly used in English than the verb effect. The AVL not only points out that this same word, with the same spelling, actually has two parts of speech; it also distinguishes the more common word from the less frequently used.

How to use the Academic Vocabulary List

First of all, you will want to enter the main AVL website. Notice that you have three main options.

- Once you register (see below), you can download the AVL lists as Excel files.

- You can use the “online interface” (the website) to find (very!!) detailed information about each word.

- You can also use the online interface to input an academic text.

The lists themselves

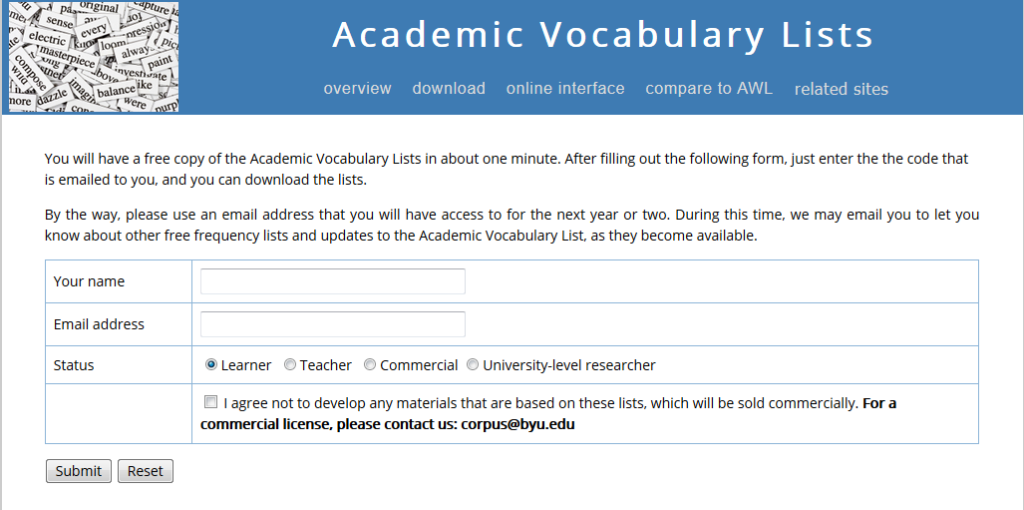

In order to access and download the Academic Vocabulary Lists, you need to register at the authors’ website, providing your name, email, and status (learner, teacher, etc.).

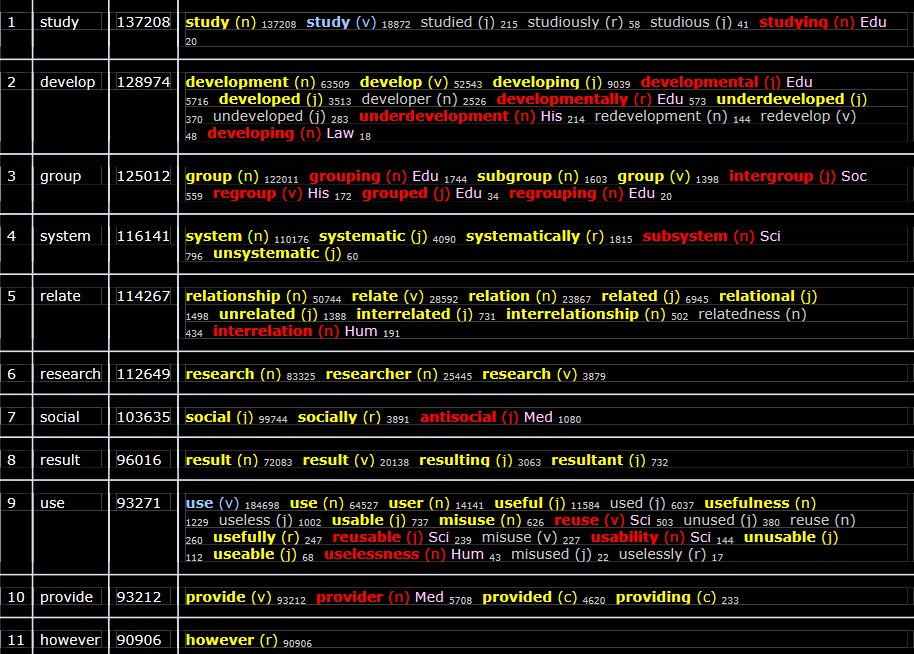

Once you have the lists, you will probably find them a little intimidating. I think the most helpful for most students is the AVL itself. This consists of 3,000 lemmas, listed in frequency order. So, for example, the top 10 words in the AVL are: study, group, system, social, provide, however, research, level, result, and include.

Also helpful, but way longer, is the Word Families list. To get the fancy color coding, you’ll need to look at the list at the website (click on Word Families). And you’ll have to figure out what the colors mean (try the Guided Tour).

Finding detailed information about words

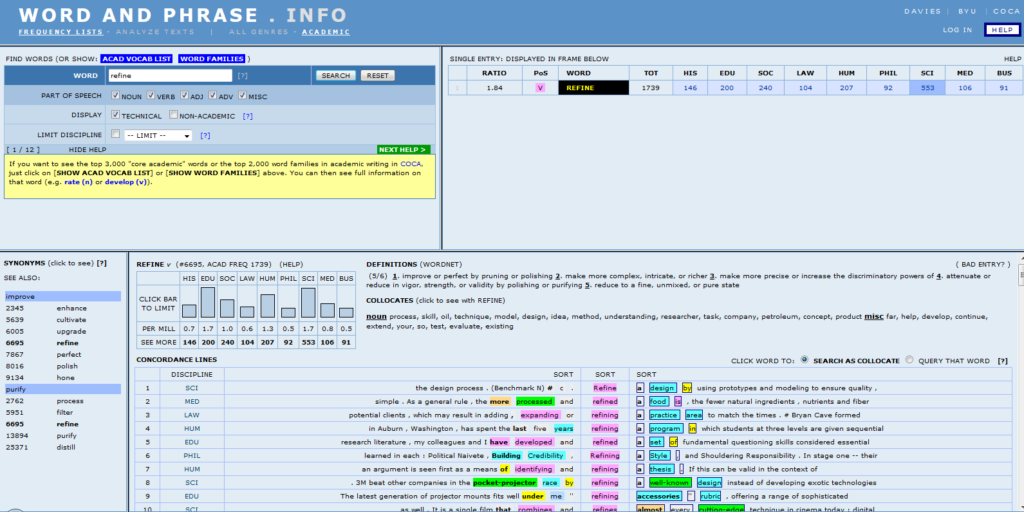

Using the website, I can find out an awful lot about individual words. Let’s say I want to find out more about the word refine. By entering the word in the Word box and clicking on Search, I can find out its part of speech (it’s a verb), what domains it appears in (most often in science), synonyms (such as enhance and cultivate), definitions, collocates (words that are commonly used with it), and specific lines of text where refine appears. Although it takes a bit of time to figure out how all this works, it’s extremely helpful information in a relatively easy-to-use format.

Using the AVL to write better

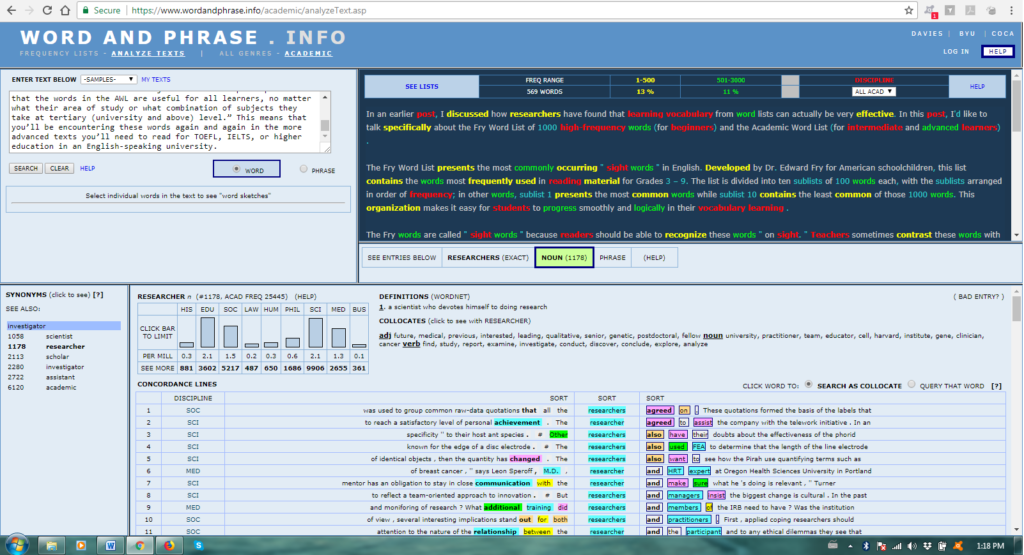

Finally, you can input any academic text, whether it’s something you’ve written or something you need to read, here. In my example below, I entered the first few paragraphs of my previous article on the vocabulary word lists and clicked on Word. The resulting text in the right side of the screen will highlight any academic words used (this would be especially helpful if you entered an academic text that you needed to read for school). You can click on individual words to get more detailed information, such as their definition or collocates. And, most helpfully for your own writing, if you click on Phrase, you can find related, and possibly “better,” phrases. For example, rather than using the phrase potent argument, you might be directed to use powerful or convincing argument, expressions that are more common in English.

The bottom line

- Because the AWL has been around longer, you are much more likely to encounter it in a variety of textbooks, websites, and teaching materials. If you are looking for online vocabulary practice exercises, just Google “Academic Word List” and you will find a plethora. If you are an intermediate-level English learner, primarily looking for an easy-to-use, well-organized word list and lots of online practice, go with the AWL.

- There are good reasons for and many advantages of using the AVL. However, as a relatively new list, there are few resources except the list and website itself (and there are apparently none in the works). Of course, the website is extremely comprehensive and the authors also have the ability to update it in the future. But, in my opinion, the AVL website is intended more for academics; there’s a steep learning curve to using it successfully. It is definitely not as user-friendly as the AWL.

- If you are an advanced English learner with a relatively large English vocabulary and especially if you need to read and write more advanced English texts, the AVL is an invaluable resource. It’s well worth the effort to learn to navigate the website and utilize its many features. It’s possible, though, that you might need an experienced user or a teacher familiar with the AVL to maximize its benefits.

How do you write a good TOEFL Writing independent essay … good enough to get a score of 4 or 5? What I’ll do in this article is show you the process I use to write an essay, with a lot of tips along the way.

♥ ♥ ♥

Essentially, the independent writing task follows the organizational structure of what teachers call “the five-paragraph essay.” The five-paragraph essay consists of:

An introductory paragraph. This contains your thesis statement … your main idea, which you will elaborate on in subsequent paragraphs. Rather than a wordy, rambling introduction, aim for two or three clearly written sentences that accurately and succinctly describe your thesis. The goal of this paragraph is to communicate very clearly to your rater what you’re going to be writing about in the rest of your essay.

Three body paragraphs. Most independent writing tasks will ask you your opinion about a topic. It is preferable to have three main points. Each point should be expanded upon in its own paragraph. The first sentence in each paragraph should be your topic sentence; it will clearly state the main idea of this paragraph. The rest of the paragraph will provide support for that idea. I have more to say about those three points in this article.

A concluding paragraph. One or two sentences restating your thesis are sufficient.

♥ ♥ ♥

In the independent writing task, you are given the topic and the timer starts counting down: 30 minutes from start to finish. Here’s the topic (TPO 20):

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

Successful people try new things and take risks rather than only doing what they know how to do well.

Use specific reasons and examples to support your answer.

♥ ♥ ♥

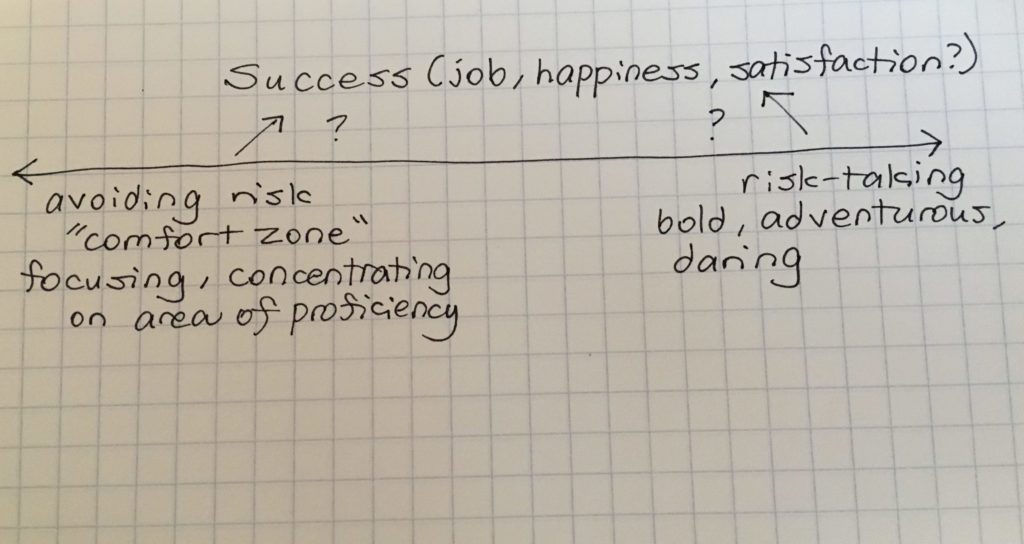

The first thing I do is to make sure I understand the question. It’s talking about what leads to success: risk-taking or sticking to what you do well. I might even illustrate this in my notes, which I’ll use before I start typing.

Notice that I’m already starting to accumulate some words or phrases that I may use in my essay.

TIP: Don’t start writing immediately! A few minutes to organize your ideas will pay off in multiple ways. Your essay will be clearer, more coherent, more focused, and easier for your rater to read.

♥ ♥ ♥

Now I need to develop a few ideas about the question: these will help me establish my stance – do I totally agree, completely disagree, or have mixed feelings?

TIP: It’s absolutely okay and often preferable to write an “it depends” essay. I have lots to say about this in this article. Unless you feel really strongly one way or the other, an “it depends” essay will reflect your own attitudes more accurately and, in my opinion, the most important objective in the whole essay-writing process is to say what you really think and believe.

♥ ♥ ♥

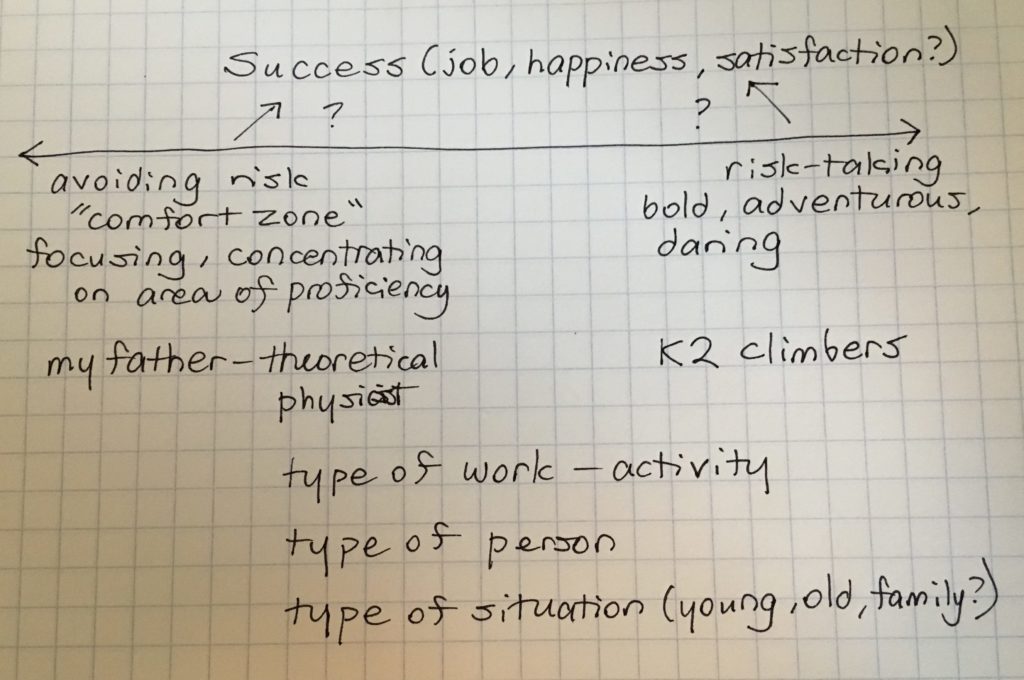

I finish up my written notes (what I would consider brainstorming) by jotting down a few preliminary ideas from my own experiences – an example of my father (not a risk-taker but a success in his profession) and some books I’ve been reading on risk-taking climbers who tried to ascend K2, the “savage mountain” in Pakistan. A bit of thought leads me to the conclusion that success comes a variety of ways, so it will depend on factors like the type of work or activity, the type of person, and maybe the type of situation the person is in.

TIP: My advice for TOEFL independent writing is the same as for independent speaking. Where do you find ideas and examples? From inside yourself. From your own experiences, your own viewpoints, your own examples. What’s really real for you is what you know best. From this reality will come the details and vocabulary you need to respond more effectively, no matter what you have to say.

♥ ♥ ♥

I’ve spent a few minutes thinking about the topic, gathering ideas, and figuring out my general approach. Now it’s time to start typing. But I don’t start off just typing the first thing that comes into my head. Instead, I type a bit of an outline, like this:

Thesis: Taking risks is sometimes necessary, but it’s not the only way to achieve success.

- To succeed in some types of work, you must focus on and master one particular thing. (father)

- Some types of work/situations are inherently risky, so people need to take risks to succeed. (climbing mountains, venture capitalism)

- The degree of risk you take depends on the type of person and the situation. (personality, age of person, family circumstances)

TIP: According to TOEFL Writing raters I have spoken to, it’s best to write five paragraphs: an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you aren’t a strong writer, those three body paragraphs may be fairly short. As long as your topic sentence is clear and you provide a few supporting details, in at least two subsequent sentences, you should be fine.

TIP: Having trouble coming up with three ideas? Think about how you might divide one idea in half. Maybe you are writing an essay supporting children wearing school uniforms and you can only come up with two points: 1) schoolchildren feel less peer pressure to be fashionable and 2) it’s easier for parents. Maybe you could divide the second point in half. One new point is that parents save money. Another new point is that parents will waste less time getting kids ready for school in the morning. Now you have three different points for your essay.

TIP: Take the time and make the effort to organize your ideas and structure your essay before you start writing. Never start writing without knowing what you’re going to say! The most important thing you can do is to make your essay easy for your rater to read and understand. Lots of words on the paper without a clear, coherent structure behind them is going to give your rater a headache and they, in turn, will give you a lower score.

♥ ♥ ♥

Here’s my finished essay.

Great adventure stories always feature heroes and heroines who are bold, daring, and fearless. Taking risks is inherent to the drama, and that’s what makes the story so compelling. However, while risk-taking may sometimes be praiseworthy and even necessary to succeed, I believe there are many times when it’s preferable to avoid risks, stay in one’s comfort zone, and achieve success without going to extremes.

First of all, many jobs require focus and concentration on one area of expertise, rather than risk-taking and trying new things. Work that is highly specialized and technical may be so difficult that success only results when people remain in their particular area of proficiency. For example, my father, a theoretical physicist, spent virtually years and years exploring just a few extremely complex and challenging problems that no scientists had yet solved.

On the other hand, some jobs, activities, or situations are inherently dangerous and cannot be completed successfully without people taking risks. These risks may be physical; mountain climbers trying to ascend Mount Everest or K2, for example, know that despite careful planning and extensive physical training, they will encounter many dangers during these pursuits. Or the risks may be monetary. Few stockbrokers or venture capitalists achieve financial success without taking risks with their investments.

All in all, whether it’s better to take risks or play it safe really depends on a person’s individual characteristics and their situation. While some people thrive on taking risks, others prefer to focus on activities and tasks that they feel comfortable doing. Both types of people are equally capable of becoming successful in their jobs or personal lives. Furthermore, as people’s circumstances change, they may feel like taking more or less risks. Young adults tend to feel more adventurous, for example, while married couples with young children may opt for more security.

So although we may enjoy reading stories about great risk-takers and adventurers, explorers and visionaries, in real life, most of us recognize that for many people and in many situations, there’s nothing wrong with sticking to the known and familiar. However we define success, whether in our jobs or the pursuit of happiness, there are many roads to its accomplishment.

♥ ♥ ♥

TIP: Many students are told that, in their introduction, they should start with a “global,” very broad statement and include all the possible choices from the topic. An example from one of my students:

People will set up different goals for new year’s resolutions. Some people consider their health as the most important task in their life, while others put time management in the first place. In my opinion, I will choose to help others in my community to be my new year’s resolution.

This is not my preference. In this essay, I chose to talk about literature that features risk-taking because I had just finished reading a book about climbing K2, the most dangerous mountain in the world. But I might also have started with a briefer introduction, for example:

Being bold and adventurous, taking risks and trying new challenges may certainly but not always lead to success. However, I believe there are many times when it’s preferable to avoid risks, stay in one’s comfort zone, and achieve one’s life goals without going to extremes.

I have two main goals in my introduction. The first, which is mandatory, is to make sure the reader understands my thesis and what I’m going to talk about in the rest of the essay. The second, which is optional but definitely preferable, is to make the reader interested in what I’m going to say. Imagine a rater reading essay after essay after essay. Do you want their eyes to glaze over or do you want to capture their attention? A good writer always aims for the second reaction.

TIP: Students are also often told that they should avoid using the first person, “I.” I disagree. If you are asked your opinion, it’s natural to use “I.” But when you use different persons (first, second, and third) in your writing, be sure that you make conscious, careful decisions about which to use. Notice that in my essay, I generally stick with the third-person, but occasionally switch to the first (I and we). Be careful not to switch randomly, especially between the second and third person. An example of what to avoid:

Students should be allowed to choose what type of room they want to live in at college. You might find it enjoyable to have a roommate, but some students like living alone. Independence is usually important when you go to college, so students should be allowed to live in a single room if they want.

TIP: Long essays are not necessarily better essays. Although less fluent writers will find it impossible to produce a lengthy essay, length alone will not necessarily guarantee a high score. My essay is 364 words, far fewer than some of my students’ work. I wrote fewer words, but I took more time organizing my ideas in the beginning, choosing my words and structures with care, and proofreading my work at the end. I recommend that you do the same. And although I once had a student whose teacher recommended initially writing about 500 words and then paring them down to about 400, I definitely don’t use that approach. I think it’s far better to spend your time organizing your ideas and carefully crafting your sentences so they don’t need to be deleted or extensively rewritten.

TIP: Keep your conclusion short and sweet. Go back to your introduction. Rephrase it and, if possible, recapture the idea that (hopefully) intrigued your reader in the beginning. For example, in my conclusion, I reiterated the idea of adventure stories.

TIP: Don’t feel that you need to write your essay “in order.” After I write down my thesis statement and the topics of my three body paragraphs, I often skip the introduction and go to the first body paragraph. It’s sometimes easier to introduce the essay when I already know what I’ve said in its body.

TIP: Always save time at the end to proofread your work. So many students’ essays that I read suffer from unnecessary language use problems (subject/verb disagreement, improper tense, incomplete sentences), punctuation mistakes, weak vocabulary or word form errors, and misspelling. I say “unnecessary” because the students, when they reread their work, recognize the errors without my pointing them out. Although your essay doesn’t have to be perfect to get a top score, you want to avoid as many of these mistakes as you can. Far better to keep your essay on the shorter side, and leave enough time to make as many corrections as you can in the last five minutes. Reading your essay aloud (in your head) may help you to identify these mistakes more easily. Error correction is also a useful skill that you can work on when practicing by yourself.

TIP: Each of your main points needs to be developed and elaborated upon. This is the “meat” of your essay, and it’s what raters will focus on. Avoid using vague reasons (“I will learn more knowledge”), unsubstantiated information (“research shows” or “the Dalai Lama says”), or trite and over-used expressions (“enhance my social skills” or “broaden my horizons”). It is much better to support your reasons with personal and authentic examples. Raters can usually tell when you are making up a story about yourself or “my friend Kenny.” Good English writing has its own “voice” … it’s genuine, not fake; individual, not generic; specific, not vague.

In my last article, I talked about general strategies to improve your reading fluency – vocabulary, comprehension, and speed. But the types of reading challenges you face in the Reading section of the TOEFL iBT require additional skills.

Skimming and Scanning

In my classroom reading classes, textbooks often gave students exercises to practice skimming and scanning.

Skimming involves reading through an entire text quickly, looking for the gist or main idea. This is a helpful skill when you are trying to decide whether a particular book or article is pertinent (for example, if you have to write a research paper), but I personally don’t use it with TOEFL articles. I just look at the title and then go straight to the first question. With only 18 minutes per reading task, I assume I’ll understand what the article is about once I go through the questions themselves, and I usually don’t need that information until I get to the final question (two main ideas). Although some teachers and study sites recommend reading the first paragraph and the first sentence of subsequent paragraphs, this isn’t a technique that’s particularly helpful for me, and it definitely takes precious time away from answering the questions.

Scanning means searching for a particular piece of information in a text. This is definitely a helpful skill for the TOEFL. If a particular question asks you about deciduous trees, for example, you will want to quickly scan the paragraph for that word. Proper names (words that are capitalized) and numbers are usually the easiest to spot quickly. Scanning is a skill that we all use in various tasks – whether we’re driving, cooking, cleaning the house, or reading a bus schedule. To improve scanning skills, play a game with a partner. Each of you should have a written text one paragraph long. Each person should find one word in the text and then exchange texts; see which of you can find the word faster.

Intensive Reading

In my last article, I talked about extensive reading – reading lots and lots of material for enjoyment and general understanding. For reading tests, however, you’ll want to focus on intensive reading skills.

When teachers cover intensive reading in a classroom, they usually spend different lessons focusing on specific reading skills, such as figuring out vocabulary words from their context, studying the way different information is presented, identifying the antecedents of pronouns, pinpointing noun-verb relationships, making predictions, and drawing inferences. These are all skills that are needed for the TOEFL iBT.

Can you self-study these types of reading skills? It’s not as easy as engaging in extensive reading. You should consider finding an English tutor, a reading class, or even an academic textbook. I have used both Real Reading (4 levels) and Reading Explorer (6 levels) in my classrooms. You might be able to find less expensive, used copies online. Reading Explorer has been revised, and the first edition of the series is much cheaper and just as good.

And, of course, you can use TOEFL Reading practice tests to hone your intensive reading skills. My preferred method of tutoring for this test is to work through a test with my student, side-by-side. If we work together, I can assess the amount of time they’re taking for each question, identify why they get wrong answers, and explain my own strategies for getting the (hopefully!) right answer.

Let’s see how that would work with a sample test. Here’s a typical TOEFL reading passage (found in TPO 1).

Timberline Vegetation on Mountains

Paragraph 1

The transition from forest to treeless tundra on a mountain slope is often a dramatic one. Within a vertical distance of just a few tens of meters, trees disappear as a life-form and are replaced by low shrubs, herbs, and grasses. This rapid zone of transition is called the upper timberline or tree line. In many semiarid areas there is also a lower timberline where the forest passes into steppe or desert at its lower edge, usually because of a lack of moisture.

Question 1

The word dramatic in the passage is closest in meaning to

- gradual

- complex

- visible

- striking

4. This is a straightforward vocabulary question that ideally my student would be able to answer in a few seconds. Obviously, to do well on a question like this, you would be familiar with the target word and all four choices. The phrases within .. just a few and rapid zone of transition also support the choice of striking.

Question 2

Where is the lower timberline mentioned in paragraph 1 likely to be found?

- In an area that has little water

- In an area that has little sunlight

- Above a transition area

- On a mountain that has an upper timberline.

1. First, you’ll scan quickly to find lower timberline, which is mentioned in the last sentence of the paragraph. To get the right answer, you’ll need to know the word semiarid (semi = partly or half; arid = dry) or else make a well-educated guess from the phrases steppe or desert (they’re usually dry places) or lack of moisture. I would hope that my student would be able to answer this question in less than a minute.

Question 3

Which of the following can be inferred from paragraph 1 about both the upper and lower timberlines?

- Both are treeless zones.

- Both mark forest boundaries.

- Both are surrounded by desert areas.

- Both suffer from a lack of moisture.

2. This question usually takes students longer because they don’t understand what a timberline is. If you’ve ever gone mountain climbing, you’ll remember that sudden transition when you emerge from a forest out into an area with no trees at all. Timber is a word for wood, and a timberline marks that boundary (line) between trees and no trees. The passage itself defines the timberline as tree line. If you know the word boundary, it’s easy to pick Choice 2. But through the process of elimination, you can eliminate the others. Since trees are mentioned, it’s not Choice 1. Deserts are only mentioned for the lower timberline, so it’s not Choice 3. And only the lower timberline suffers from lack of moisture, so we can eliminate Choice 4.

Paragraph 2

The upper timberline, like the snow line, is highest in the tropics and lowest in the Polar Regions. It ranges from sea level in the Polar Regions to 4,500 meters in the dry subtropics and 3,500-4,500 meters in the moist tropics. Timberline trees are normally evergreens, suggesting that these have some advantage over deciduous trees (those that lose their leaves) in the extreme environments of the upper timberline. There are some areas, however, where broadleaf deciduous trees form the timberline. Species of birch, for example, may occur at the timberline in parts of the Himalayas.

Question 4

Paragraph 2 supports which of the following statements about deciduous trees?

- They cannot grow in cold climates.

- They do not exist at the upper timberline.

- They are less likely than evergreens to survive at the upper timberline.

- They do not require as much moisture as evergreens do.

3. First of all, a quick scan through the paragraph to find the word deciduous. TOEFL doesn’t expect you to know that word, so they provide the definition in parentheses. This single sentence should provide you with the answer. Timberline trees are normally (usually) evergreens, not deciduous trees, at the upper timberline. It doesn’t say timberline trees are always evergreens, so Choices 1 and 2 wrong; in fact, the following sentence confirms that some deciduous trees do form the timberline. And there’s nothing about moisture in this paragraph. If you don’t waste your time reading the whole paragraph, and just focus on the one single sentence, you should be able to answer this question quickly.

Paragraph 3

At the upper timberline the trees begin to become twisted and deformed. This is particularly true for trees in the middle and upper latitudes, which tend to attain greater heights on ridges, whereas in the tropics the trees reach their greater heights in the valleys. This is because middle- and upper- latitude timberlines are strongly influenced by the duration and depth of the snow cover. As the snow is deeper and lasts longer in the valleys, trees tend to attain greater heights on the ridges, even though they are more exposed to high-velocity winds and poor, thin soils there. In the tropics, the valleys appear to be more favorable because they are less prone to dry out, they have less frost, and they have deeper soils.

Question 5

The word attain in the passage is closest in meaning to

- require

- resist

- achieve

- endure

3. When answering a question like this, I often substitute my own word in place of the target word before I read the four options. In this case, I thought of trees tend to reach greater heights. Then when I looked at the options, achieve was the obvious choice. Again, this is a relatively easy vocabulary question that students should be able to answer quickly. You don’t need to read the whole paragraph to understand the meaning; just the phrase inside the commas should be enough.

Question 6

The word they in the passage refers to

- valleys

- trees

- heights

- ridges

2. Again, you don’t need to read the whole passage to get the correct answer. Look for the subject of the phrase, trees tend to attain greater heights on the ridges. Heights is the direct object; ridges is the object of a preposition. The subject of the main clause is trees, and therefore it’s most likely that they will be the subject of the dependent clause as well. They, the trees, are what are more exposed to winds and poor soils there on the ridges.

Question 7

The word prone in the passage is closest in meaning to

- adapted

- likely

- difficult

- resistant

2. Another vocabulary question and, in this case, the choice likely came to my mind before I even read the options. I think you should know the word prone, which is commonly used in English. But if not, you could try substituting the other choices. None of them really sounds right.

Question 8

According to paragraph 3, which of the following is true of trees in the middle and upper latitudes?

- Tree growth is negatively affected by the snow cover in valleys

- Tree growth is greater in valleys than on ridges.

- Tree growth on ridges is not affected by high-velocity winds.

- Tree growth lasts longer in those latitudes than it does in the tropics.

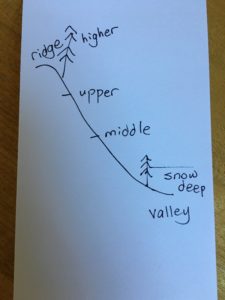

1. Unlike most of the questions, this is one where you’ll need to do a close reading of the whole paragraph. What helped me answer this question was a quick little sketch. Don’t be afraid to do this if it helps you create a better picture in your mind. This picture helped me to visualize why snow would be a problem for the trees. My other difficulty was the reading passage’s use of as (in as the snow is deeper and lasts longer …). I usually use as to mean when or during (As I was getting on the bus, I saw a friend) and not as since or because, as it’s used in this passage. This is a question that took me several minutes to be sure of my answer.

Paragraph 4

There is still no universally agreed-on explanation for why there should be such a dramatic cessation of tree growth at the upper timberline. Various environmental factors may play a role. Too much snow, for example, can smother trees, and avalanches and snow creep can damage or destroy them. Late-lying snow reduces the effective growing season to the point where seedlings cannot establish themselves. Wind velocity also increases with altitude and may cause serious stress for trees, as is made evident by the deformed shapes at high altitudes. Some scientists have proposed that the presence of increasing levels of ultraviolet light with elevation may play a role, while browsing and grazing animals like the ibex may be another contributing factor. Probably the most important environmental factor is temperature, for if the growing season is too short and temperatures are too low, tree shoots and buds cannot mature sufficiently to survive the winter months.

Question 9

Which of the sentences below best express the essential information in the highlighted sentence in the passage? Incorrect choices change the meaning in important ways or leave out essential information.

- Because of their deformed shapes at high altitudes, trees are not likely to be seriously harmed by the strong winds typical of those altitudes.

- As altitude increases, the velocity of winds increase, leading to a serious decrease in the number of trees found at high altitudes.

- The deformed shapes of trees at high altitudes show that wind velocity, which increases with altitude, can cause serious hardship for trees.

- Increased wind velocity at high altitudes deforms the shapes of trees, and this may cause serious stress for trees.

3. The good news is that if you already did a close reading of the paragraph, you shouldn’t need to read it carefully again. You only need to look carefully at this one sentence. Try rewording it yourself before looking at the options. Wind is stronger the higher you go; this can stress the trees; you can see this because they’re deformed. Once you do that, you can quickly eliminate the first and second answer. The fourth is not good because it states that the deformed shape causes stress, whereas the text says it’s the wind that stresses the trees. If you are able to paraphrase the original sentence successfully and understand the meaning of the four choices, this should be a relatively quick question to answer. But to do that, you need a good understanding of more complex grammatical structures. One strategy that I recommend is identifying the subject(s), verb(s), direct object(s). For example, in Choice 3, I mentally read:

(the deformed) shapes (of trees at high altitudes) show —> wind velocity (which may increase with altitude) can cause (serious) hardship (for trees).

Question 10

In paragraph 4, what is the author’s main purpose in the discussion of the dramatic cessation of tree growth at the upper timberline?

- To argue that none of several environment factors that are believed to contribute to that phenomenon do in fact play a role in causing it.

- To argue in support of one particular explanation of that phenomenon against several competing explanations

- To explain why the primary environmental factor responsible for that phenomenon has not yet been identified

- To present several environmental factors that may contribute to a satisfactory explanation of that phenomenon

4. My strategy for answering this question relatively rapidly is to skim through the whole paragraph. I see from the first sentence that “there’s no universally agreed-on explanation,” so that sets the stage for a discussion of several explanations. And a quick reading gives me “various environmental factors,” including snow, wind velocity, ultraviolet light, animals, and temperature. These are each mentioned in passing, with only “the most important environmental factor” (temperature) providing a bias toward one explanation. But there’s no other indication that the author or most scientists favor one explanation rather than another. Choice 4 best reflects this reading of the paragraph. Answering this question should be relatively easy, although it will be necessary to at least skim through the whole paragraph rather than focus on only one sentence.

Paragraphs 5 and 6

Above the tree line there is a zone that is generally called alpine tundra. ![]() Immediately adjacent to the timberline, the tundra consists of a fairly complete cover of low-lying shrubs, herbs, and grasses, while higher up the number and diversity of species decrease until there is much bare ground with occasional mosses and lichens and some prostrate cushion plants.

Immediately adjacent to the timberline, the tundra consists of a fairly complete cover of low-lying shrubs, herbs, and grasses, while higher up the number and diversity of species decrease until there is much bare ground with occasional mosses and lichens and some prostrate cushion plants. ![]() Some plants can even survive in favorable microhabitats above the snow line. The highest plants in the world occur at around 6,100 meters on Makalu in the Himalayas.

Some plants can even survive in favorable microhabitats above the snow line. The highest plants in the world occur at around 6,100 meters on Makalu in the Himalayas. ![]() At this great height, rocks, warmed by the sun, melt small snowdrifts.

At this great height, rocks, warmed by the sun, melt small snowdrifts. ![]()

The most striking characteristic of the plants of the alpine zone is their low growth form. This enables them to avoid the worst rigors of high winds and permits them to make use of the higher temperatures immediately adjacent to the ground surface. In an area where low temperatures are limiting to life, the importance of the additional heat near the surface is crucial. The low growth form can also permit the plants to take advantage of the insulation provided by a winter snow cover. In the equatorial mountains the low growth form is less prevalent.

Question 11

The word prevalent in the passage is closest in meaning to

- predictable

- widespread

- successful

- developed

2. Yet another vocabulary question which should be quickly and easily answered if you know the target word. My substitute word was common, and widespread is a synonym of that. It is interesting to me that the first two words, dramatic and attain, appear on the Academic Word List, while the second two, prone and prevalent, do not. This indicates to me that while it’s certainly a good idea to study vocabulary words from a well-recognized word list, extensive reading from a variety of sources is essential as well. Not all the words you need will be found on a single list.

Question 12

According to paragraph 6, all of the following statements are true of plants in the alpine zone EXCEPT:

- Because they are low, they are less exposed to strong winds.

- Because they are low, the winter snow cover gives them more protection from the extreme cold.

- In the equatorial mountains, they tend to be lower than in mountains elsewhere.

- Their low growth form keeps them closer to the ground, where there is more heat than further up.

3. Questions like this always confuse me and I have to keep in mind what they’re really asking, that is … which of these statements is FALSE! Again, I have to make a quick skim of the whole paragraph, focusing on the important words; phrases like avoid high winds, make use of higher temperatures [near] the ground, insulation by snow all mirror Choices 1, 2, and 4. To make sure the statement in Choice 3 is false, I closely read the last sentence in the paragraph (the only one that mentions equatorial mountains). It doesn’t say anything about the low growth form being lower, just less prevalent. Even if I didn’t know what prevalent meant, I would choose that option anyway, because the other three choices all seem true to me.

Question 13

Look at the four squares [ ![]() ] that indicate where the following sentence could be added to the passage.

] that indicate where the following sentence could be added to the passage.

This explains how, for example, alpine cushion plants have been found growing at an altitude of 6,180 meters.

Where would the sentence best fit? Click on a square to add the sentence to the passage.

4. I hate this kind of question! What I will do, before reading the paragraph, is to look closely at the sentence itself. This explains how [some sort of explanation needs to precede this sentence] … for example, alpine cushion plants [since this is an example, alpine cushion plants probably haven’t already been mentioned] have been found growing at an altitude of 6,180 meters [this is a high altitude]. Now I’ll go back, read through the whole paragraph, and see where that information might fit best. Choice 1 makes no sense; the preceding sentence describes a situation, not an explanation. Choice 2? Oops, they mention cushion plants, so that destroys my hypothesis but the plants are prostrate. I need to know that vocabulary word to make sense of the passage: it means to be lying face down, in a position of weakness. But it doesn’t make sense to follow that mention of cushion plants with another mention of cushion plants as an example. Reading on, I get to Choice 3, but the preceding sentence isn’t an explanation, so the sentence doesn’t fit. And now, Choice 4 … this had better be the right one since I’ve eliminated the others. It indicates that we’re at a great height (as the sentence said) and that rocks are hot enough to melt the snow. Thus, the presence of these hot rocks explains why some cushion plants can thrive here in this microclimate, even when they were prostrate further down the mountain.

Question 14

An introductory sentence for a brief summary of the passage is provided below. Complete the summary by selecting the THREE answer choices that express the most important ideas in the passage. Some sentences do not belong in the summary because they express ideas that are not presented in the passage or are minor ideas in the passage.

At the timberline, whether upper or lower, there is a profound change in the growth of trees and other plants.

- Birch is one of the few species of tree that can survive in the extreme environments of the upper timberline.

- The temperature at the upper timberline is probably more important in preventing tree growth than factors such as the amount of snowfall or the force of winds.

- High levels of ultraviolet light most likely play a greater role in determining tree growth at the upper timberline than do grazing animals such as the ibex.

- There is no agreement among scientists as to exactly why plant growth is sharply different above and below the upper timberline.

- The geographical location of an upper timberline has an impact on both the types of trees found there and their physical characteristics.

- Despite being adjacent to the timberline, the alpine tundra is an area where certain kinds of low trees can endure high winds and very low temperatures.

2, 4, 5. By the time you get ready to answer this final question, you should have a good sense of the whole reading passage, even though you didn’t read it word for word. Three choices are right, and three choices are wrong. Therefore, we should use two strategies together … identifying those statements that are minor details or not true or both, and those statements that seem to accurately reflect main ideas in the text. With this method, I quickly eliminate Choice 1 (minor detail in Paragraph 2) and Choice 3 (minor detail in Paragraph 4, and not true either).

With that being said, I don’t agree with the answers given in my TPO app (they say 4, 5, and 6), so either they’ve made a mistake, or I have. I picked Choice 2 because a whole paragraph (4) is devoted to factors affecting tree growth, and it’s stated that “the most important environmental factor is temperature.” I picked Choice 4 because we know plant growth is sharply different (dramatically different!) and aren’t given one definitive explanation for it. And Choice 5 was an obvious choice; the text mentioned various geographical locations and the differences associated with them. I rejected Choice 6 because the very first sentence mentioned the “treeless tundra” and although two paragraphs discuss the tundra, there is no mention of trees there, just shrubs, herbs, and grasses.

The final question counts two points, so spend a bit of time on it. Even if you don’t get all three choices correct, at least try to eliminate a couple and make your best guess on the remaining ones.

General Advice

Hopefully, the section above has given you an idea of how I approach a reading passage on the TOEFL and its associated questions. In terms of overall strategies, I recommend:

- Watch your time. Mentally divide your time into 18-minute segments and don’t take longer than 18 minutes on any one section. You can always go back if you have remaining time at the end.

- Answer every question. You don’t lose points for wrong answers.

- Expect that some questions can be answered really quickly and some more slowly. Don’t panic if you hit a tough one.

- If you are really stumped for an answer, at least eliminate one or two choices that are obviously wrong and then make your best guess.

- Use scanning to quickly locate the information you need. As you can see from the questions above, many could be answered by looking at just a single sentence.

- Although many websites and teachers recommend skimming the whole passage at the beginning, I don’t. I think it’s a waste of time. Reading the title is enough. You’ll never have enough time to read the whole article carefully, so don’t even try. By working through each question, you should have a fairly good understanding of the whole passage by the time you get to the last question.

- Be careful! To throw test takers off, test writers use “distractors” by including a word or phrase from the passage. You can see that in Choice 3 of Question 12.

Although TOEFL Reading is a challenging test, I believe it’s a fairly good tool to assess reading ability. These are skills that you’ll need for the future when you tackle academic texts in English. Reading skills won’t improve overnight, but with steady, sustained work including vocabulary acquisition, extensive reading, speed reading, intensive reading, and TOEFL-specific practice, you should get your goal score sooner or later.

Edited to add: With the “new” shorter TOEFL iBT, there are fewer questions per reading section than in the TPO practice tests. However, the same question types have been retained. If there are any further revisions to the test, just remember to take your total reading time, divide it by the number of reading passages, and use that time per reading passage to determine your progress through the test. Timing is critical; every question should be answered!

How can I improve my English reading skills, especially when it comes to the academic reading in the TOEFL iBT?

Because there are so many different strategies I recommend, I’ll give my advice in two separate articles — the first dealing with general strategies and the second with skills needed for reading tests.

Vocabulary

I’ve already written a series of articles about vocabulary starting with this one. And in my opinion, when it comes to reading quickly for general comprehension (not what we call a close reading), knowledge of vocabulary is much more important than knowledge of grammar. From my own experience reading French for many years, I don’t pay much attention to grammatical structures as long as I get a basic sense of subject/verb/object, past/present/future, and basic parts of speech. But if I don’t know a word, it can make all the difference in whether I understand what a text is saying.

Vocabulary knowledge is also essential for doing well on the Reading section of the TOEFL, as I’ll describe in my next article. Thus, a fundamental part of improving reading fluency will focus on continually acquiring new vocabulary. Don’t stop! You will never ever know enough words.

Extensive Reading

One of the first things I ask my students is whether they enjoy reading in their native language.

Some people are “ born readers” and some aren’t. Although I think everyone can increase their love of reading, given the right reading material, I don’t think you can essentially change your attitude. If you do love to read, you’re in luck. As an English and American Literature major, I can tell you that some of the greatest works in world literature have been written in English. Being able to read them in their original language rather than a translation may be all the motivation you need to work hard on your reading skills.

But whether you love reading or not, reading should be essentially enjoyable. Nothing kills the pleasure like struggling to understand every other word. This is why teaching professionals advocate extensive reading.

Extensive reading happens when a reader pays attention to the meaning of the words, and not the words themselves. And studies have shown that for this to occur, readers need to be familiar with 95 to 99% of the words they encounter.

Think about that. You should know (in the sense that you have a good understanding of the meaning of a word; if “inner translation” is going on in your head, it’s rapid and almost unnoticeable) at least 95 out of every 100 words you read. Ideally, you would know 99 of them.

But here’s the problem. If you aren’t a very good reader, how do you find material that’s easy enough to read? In my classroom, my reading students used graded readers, which are written for adult learners of English and come in a range of reading levels based on vocabulary and sentence structure. You may be fortunate enough to have access to these kinds of readers through a public or university library or you may try to locate them online. Well-known publishers of graded readers include Cambridge, Oxford, Macmillan, Pearson, and Scholastic. This is a chart that gives some common series and their levels. If you want to assess your current reading level, try this placement test. Another option, if you don’t have access to graded readers for adults, is to read chapter books written for English-speaking children. Although they may seem a bit babyish, these books are ideal for beginning and intermediate readers. I particularly like Cynthia Rylant’s series: Henry and Mudge (a boy and his dog) and Mr. Putter & Tabby (an elderly man and his cat).

A few recommendations made by the researchers Nation and Wang include:

- Read at least one graded reader each week.

- Read at least five readers at one level before advancing to the next level.

- Read at least 15 – 20 graded readers each year, and preferably 30.

- Read more books at the later levels than the earlier levels.

A resource you can use to evaluate online reading material is to copy and paste a sample of the text into a readability checker. Texts are assigned a grade level corresponding to grades in US schools (with 12th being the highest). For comparison, my blog article Give or Get? is scored Grade 6 (fairly easy to read) while the TOEFL reading passage that I’m going to use in my next article is Grade 12 (fairly difficult to read).

Speed Reading

Reading quickly is not going to help you much with the TOEFL iBT Reading section (although it will help somewhat with the Speaking and Writing integrated tasks); we’ll talk about that in the next article. But if you need English for academic study or a career, you will want to avoid plodding along when you read. Being able to pick up your pace will make your life a lot easier!

To test your current reading speed, just Google “testing reading speed” and you’ll find lots of different sites. I tried this one at the Wall Street Journal and found my reading speed ranged from 432 – 492 words per minute, with 100% comprehension.

Obviously, your reading speed is going to be affected by the difficulty of the text (including vocabulary, structures, and content). A reasonable reading goal for easy reading material (known words, basic grammatical structures, simple content) is around 250 words per minute. And you need to read carefully enough that you’re able to understand and remember what you read … this is why tests of reading speed include comprehension questions at the end.

One of the best ways to improve reading speed is to use graded readers that are a much easier level for you. Here you focus not on meaning (which improves vocabulary and understanding) but on speed alone. Use a stopwatch to test your speed and don’t be afraid to repeat reading the same material over and over. Keep a log of your progress and make a game of the whole process.

Finally, a bit of advice from my own experience reading French. Even now, after 40 years of reading French, I find that with challenging texts (those written for French-speaking adults, including authors like Proust who challenge even French readers), I often activate my “inner translator.” In other words, every word I read in French gets mentally translated into English before it’s processed. I have to make a really conscious effort to avoid that to pick up my reading speed.

So, we’ve talked about reading a lot and reading quickly. In the next article, we’ll talk about reading closely and carefully, especially in the context of a specific TOEFL Reading passage.

How can I get a better score on the TOEFL iBT Listening section?

After hearing that question from a number of students, I decided to take a few practice tests myself. No better way to figure out how to tackle a challenge than to actually do it yourself! And here are some thoughts I have about the test.

What Type of Learner Are You?

Most people are aware that there are different types of learners, classified by how they prefer to receive and process information. Auditory learners like to listen; visual learners like to see; kinesthetic learners like to touch. You may have already figured out what type you are.

I’m a visual learner. If someone gives me directions orally, I usually get them mixed up. I much prefer a set of written directions, or a map. Thus, I find listening tasks more difficult to follow. Lectures are easier for me if I’m given a handout or provided with an accompanying PowerPoint.

You can’t change the type of learner you are. Just be aware that if you aren’t an auditory learner, any listening task, whether in English or your native language, is going to present a bigger challenge. And this may affect your approach.

Notes or No Notes?

I have had a few students who don’t take notes, ever. Not in university, and not on the TOEFL. But, as a visual learner, this is not my approach. Taking notes really helps me not only to put what I hear into a visual format, but also to focus better on the content. I’m not sure I could remember what I heard if I didn’t have something written down.

So unless you’re an auditory learner with an excellent memory, I recommend that you take notes. However, note-taking may well distract you from actually listening, and therefore must be done strategically.

How to Take Notes?

Personally, I don’t believe there’s one right way to take notes. I’ve had students who’ve mentioned a particular note-taking method that an online site, study guide, teacher, or friend who got a high score has recommended. But I say … find the method that works for you. It’s like when you’re trying to lose weight. Go online and you’ll find thousands of diets that have plenty of followers all saying that this is the perfect way to lose weight. What they’ve found, actually, is the right way for them, but maybe not for you.

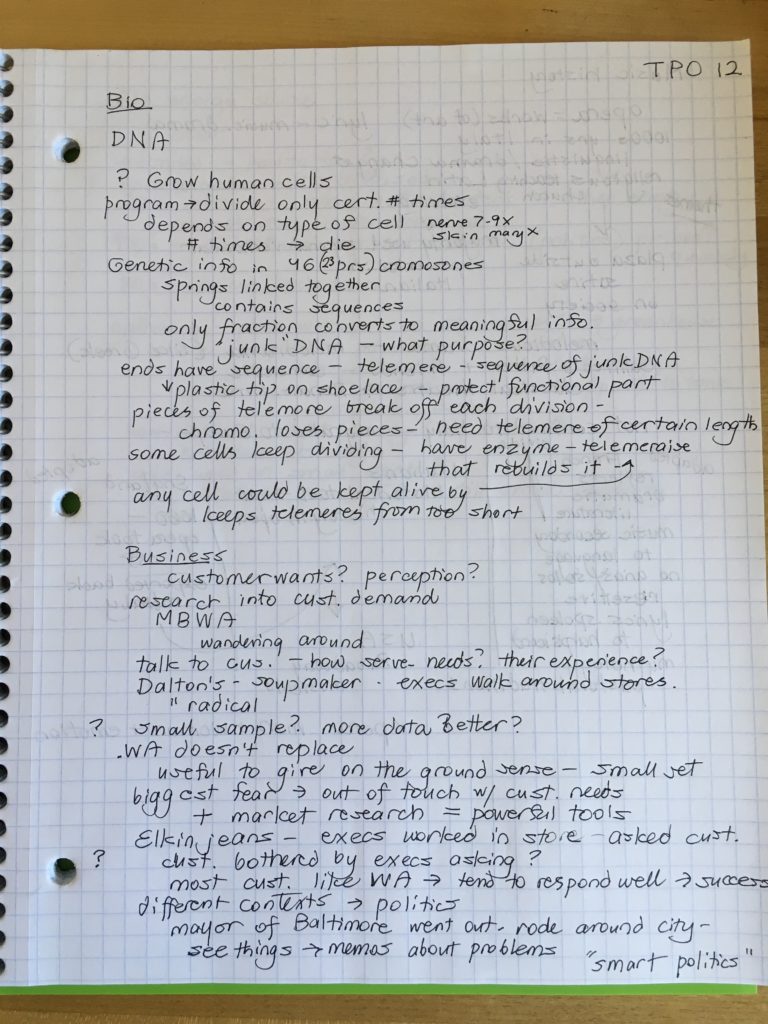

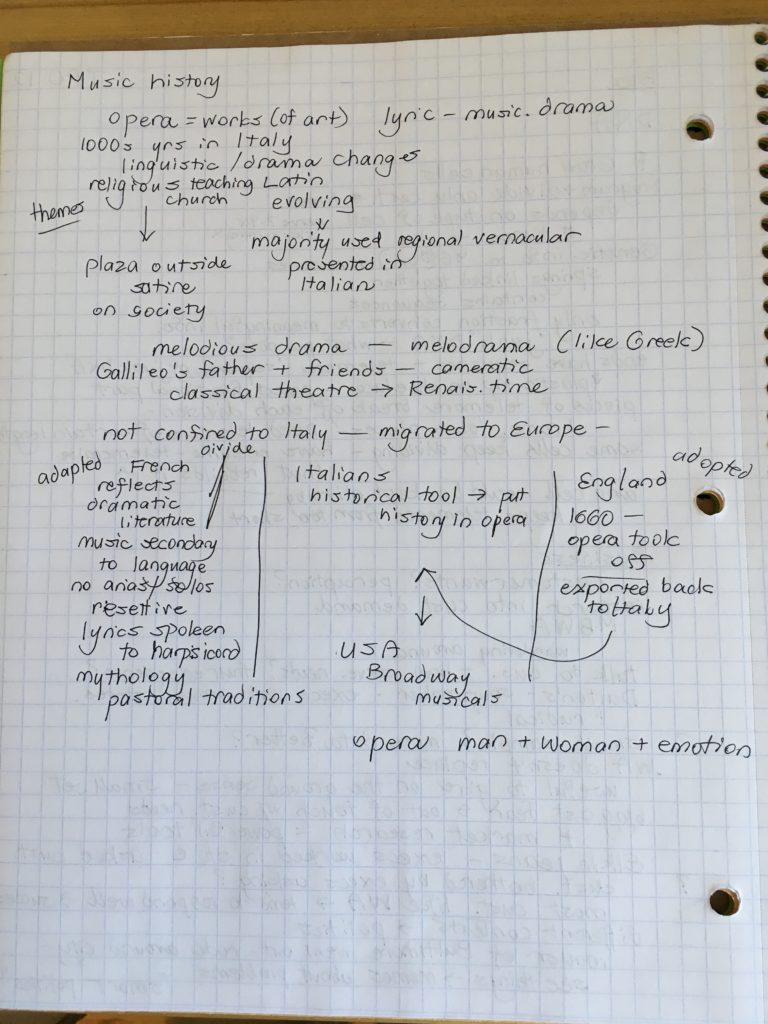

So, through practice, identify what type of note-taking works best for you. Ideas to consider:

- Write at least some of your notes in your native language, if that is quicker or more legible for you. No one will look at your notes, so you won’t be judged negatively for this.

- Practice writing quickly. I have lots of students who tell me that they can’t read their own handwriting. It’s worth making some effort to improve your handwriting. I am a big believer in italic handwriting.

- Use abbreviations, arrows, mathematical signs (like equal or plus signs), and lines to more quickly clarify information.

- Listen for “themes” of the lecture and organize your notes accordingly. For example, if the professor is going to describe two types of something, divide your paper in half with a line. If you’re going to hear about a process, use arrows or numbers to connect each step.

Here are two sample pages of notes that I took for three lectures (biology, business, and music history) from TPO (TOEFL Practice Online) 12.

Some Final Words

When teachers teach listening skills in the classroom, they often use “pre-listening” activities to give the students some context and stimulate some thoughts about the topic before they listen. Unfortunately, this isn’t going to happen on TOEFL … you won’t have any idea what the subject is until the lecture or conversation begins.

To provide that all-important context, I think a strong academic background in a variety of subjects gives you a big advantage. I found that my limited but basic prior knowledge of different subjects really helped me. For example, in the biology lecture on DNA, I had just encountered the word telomere from watching a Great Courses lecture series on the mind-body connection. The history of the opera made more sense to me because I already knew what an aria was and understood the general pattern in European history of culture moving from religious (church) settings to a more secular context. Although you won’t know what subjects you’ll encounter in the TOEFL lectures, the more widely you read and the greater variety of listening resources you use, the better prepared you’ll be to understand at least some of the references in what you hear.

Finally, remember that listening skills will help you not just in the Listening section but also in the four integrated Speaking tasks and the integrated Writing task. Your scores on those parts of the test are going to depend heavily on your ability to understand what you hear. Therefore, when it comes to studying English, you should definitely be all ears!

For more resources on improving your listening skills, see this article.

Numbers are one of the first things we learn in a foreign language, maybe because they play such an important role in our everyday life. And, for the same reason, there are lots of phrases with numbers that can be very useful in understanding and expressing yourself in English.

1 to 10. This is the most common way to rank various things in English. Maybe it’s the same in your country? With this scale, 1 is usually the worst and 10 the best. For example, every time my family went on vacation, I would ask my kids to rate the trip from 1 to 10, with 1 being a complete disaster (fortunately that never happened) and 10 being absolutely wonderful in every respect.

Perfect 10. I think this expression originated from the Olympic games, where some athletes such as gymnasts and ice skaters perform routines for which 10 would be a perfect score. In this case, though, it relates to people using a scale of 1 – 10 to rank other people in terms of their attractiveness. So, in the movie 10, the plot revolves around a man who falls in love with a woman he considers a perfect 10.

A dozen. Although industry and science employ the metric system in the US, most citizens are more familiar with the imperial system, which often uses 12 instead of 10 as a base (for example, there are 12 inches in a foot). Maybe for this reason, we often find items like eggs packaged in groups of 12 … that’s a dozen. A half-dozen would be six.

A baker’s dozen. Thirteen or 12 + 1. This comes from the idea that a baker might, as a sign of good will, throw in an extra donut or cookie with your order if you asked for a dozen.

Six of/to one, half a dozen of/to another (the other). This expression, which can be stated various ways, is a little weird, but it basically means “it’s all one and the same.” If you’ve paid attention, you will remember that six equals half a dozen. So maybe someone will ask you, “Do you want to eat at McDonald’s or KFC?” and you’ll answer, “It’s six to one, half a dozen to the other,” which just means that you don’t care and it’s all the same to you … one choice is six and the other choice is half a dozen.

Zero. This can be used as a noun to mean something or someone that is a nothing, a nonentity, or a complete failure. For example, “This day has been a complete zero. I haven’t accomplished anything.” Or, as my former supervisor used to say if a student didn’t like me, “To some folks, you’re a hero and to others, you’re a zero.”

50/50. Lots of times we use probabilities or percentages to express our ideas. If you are 50/50 about something, that means you aren’t sure what you think. Someone might say, “I’m 100% in favor of going out to the movies,” and you might say, “I dunno. I’m 50/50. I’d like to go, but it’s raining and it might be more fun to stay home and watch Netflix.”

The odds are … In the same way, we often refer to betting expressions. This would mean the same as saying, “the chances are …” For example, “the odds are in his favor for getting that new job.” On the other hand, if the odds are nil, his chances are zero.

One in a … This is a common expression to talk about something or someone that’s quite rare or very special. The higher the number, the more special or unusual the thing is, so the most common expression is probably “one in a million.”

Zillion, gazillion. In English, real very big numbers include million, billion, and trillion. But we often use the fictional, made-up numbers zillion or gazillion to describe a very large number of things. For example, I have a zillion things to do before we go on vacation. Or, I’ve already told you a gazillion times that I don’t want to give a speech in public.

Umpteen. Like zillion and gazillion, umpteen is a made-up number that is often used humorously to describe how many times something has to be or has been done. Unlike the real numbers thirteen through nineteen, umpteen describes some number larger than all of them. For example, he reassured her for the umpteenth time that she didn’t look fat in that dress. Or, he told me umpteen times how to fix my computer problem but I still didn’t understand.

I’ve got your number. A common idiom in English, this means that you’ve figured someone out and they can’t fool you. We might also say, “I’ve got my eye on you,” or “I know what you’re up to.” You’ve seen through this person’s tricks and strategies and you have figured out their real intention.

In an earlier post, I talked about some strategies to use when asked for your opinion, especially in a test like TOEFL or IELTS. I’d like to elaborate on this topic, with many thanks to my long-time student Sam who spent a lot of time discussing these ideas with me.

Let’s say you’re given the following question:

Some people prefer to watch movies or films at a cinema or movie theatre. Others prefer to watch them at home. Which do you prefer and why?

So now what do you do?

First of all, many students ask me how they can generate ideas, especially when they have a very short time to prepare an answer. My most important piece of advice is to answer truthfully. If you say what you really think, all those ideas will be in your head already. And your response will sound more real, more genuine, and more personal … it won’t sound like everyone else’s.

Once you have some ideas, how do you present them? There are three different strategies you can choose.

The 100% Method

With this method, you choose one side and all the content in your answer supports that choice. Many people think you need two reasons in a 45-second response, but this simply isn’t true. You can provide one good, well-developed reason or multiple reasons … whatever comes into your mind that you’re able to talk about. A 100% answer might sound like this:

Well, I think I’d rather watch movies at home because I’m a parent of small children and we don’t have a lot of extra money for a babysitter. So a couple of nights a week, my husband and I will make sure that the kids get to bed on time and then we’ll curl up on the couch and watch a movie on Netflix. We can pop some popcorn and relax and if one of the kids wakes up we can pause the movie and take care of the situation and then go back to the movie. And if we get really tired, we can stop the movie and just finish it the next evening.

The 100% Method is also frequently used when answering an essay question such as the TOEFL independent writing task. Most test-takers choose one option or the other and then focus on three reasons (one per paragraph) supporting that choice. But as you’ll see below, although this is the most common method, it’s not the only way to write this kind of essay; and you’ll probably impress your rater if you opt for another method that’s not quite so typical.

The 90/10 Method

With the 90/10 Method, you spend 90% of your time talking about the option that you choose, but you also acknowledge the other choice. This is a good method to use if there are certain reasons or circumstances when you might prefer the other option, but you don’t want to spend too much time talking about them. A 90/10 answer could go as follows:

You know, on special occasions when I’m going out with my whole family, it’s fun to watch a movie in the movie theatre. But most of the time, I watch movies at home. It’s just easier and more relaxing. I don’t have to pay a lot of money on tickets and parking, and I don’t have to spend time travelling to the movie theatre … because where I live, the nearest movie theatre is 10 miles away. And I have more choices, because at our movie theatre, they only play one movie each week, and maybe it’s not a movie I’m interested in. If I stream a movie on my computer, I can watch pretty much anything I want.

You can also use this same method if you decide to spend most of your time talking about the option you wouldn’t choose (and this is a perfectly acceptable way to answer this type of question). So, for example:

I don’t mind watching movies at home, but I really never go to the movie theatre. Actually, I haven’t gone to a movie at the movie theatre for years. It seems like if I go during the daytime, I always get a headache when I come back out of the dark theatre into the daylight. And movies at night definitely don’t work for me because I go to bed really early. I guess I also spend a lot of time worrying about whether the tickets will be sold out and then, when I’m seated, if someone is going to sit in front of me and block my view. I just find going to the theatre kind of stressful and unpleasant, I guess.

One thing to note is that the 90/10 Method is often used when we’re writing a persuasive or argumentative or opinion essay (as is often the case in TOEFL or IELTS). This type of writing is usually more convincing (and therefore “better”) when we present an opposing argument and then proceed to counter it with our own opinion. Each paragraph will always focus on your own beliefs, but you’ll acknowledge the “other side.” For example, an essay for the TOEFL independent writing task might be organized as follows:

Opening Paragraph Thesis Statement: Although there are reasons why people might like movies in the movie theatre, I prefer to watch them at home.

Body Paragraph 1: Sometimes discount tickets are available, but movies at home are usually cheaper. The paragraph then elaborates on the savings you get (not paying for tickets, parking, transportation, babysitting, food when watching the movie, etc.)

Body Paragraph 2: On special occasions it’s fun to go to the theatre, but it’s a lot more convenient for me to watch movies at home. You then cite several conveniences (can be a last-minute decision, more comfortable surroundings, no travel to and from theatre).

Body Paragraph 3: If you live in a big city you might be able to see a wide variety of movies, but I don’t have that option where I live. You describe how your movie theatre selections are limited while you have tons of options (use some specific examples) at home.

The 50/50 Method

With this method, you spend half your time talking about one option and half the time talking about the other. You can also call this the “it depends” method.

To ensure coherence and focus in your answer (especially if you have a very limited time), it’s essential to center your response around ONE factor only. What does your choice depend on? Make that clear in your answer. Here’s an example:

Well, whether I watch a movie at home or in a theatre really depends on whether it’s a weekday or weekend. When I have to go to work the next day, I can’t stay out too late and I also don’t have enough time to travel to and from the movie theatre. So on a weekday, my wife and I really like to put the kids to bed early and snuggle up on the couch to watch Netflix. On the other hand, on a Friday or Saturday night, we’ll get a babysitter and have a special date night. One of our favorite things to do is to have dinner and then go see a film.

This method is equally effective in a written essay, as long as you organize your answer carefully in the beginning and make sure you follow the right structure. To expand, just think of more factors that your choice depends on. For example:

Opening Paragraph Thesis Statement: Whether I watch a movie at home or in the movie theatre depends on several factors.

Body Paragraph 1: Time of the week. Weekdays I stay at home. Weekends I go to the theatre.

Body Paragraph 2: Type of movie. I like to watch romantic and/or sad movies at home (embarrassing to watch love scenes with strangers, I cry easily). I like to watch action movies in the theatre (special effects, surround sound, sharing the audience’s excitement).

Body Paragraph 3: Who I’m with. When I’m alone, I watch movies at home (I don’t like to go out by myself, feel uncomfortable being by myself in a theatre). When I’m with my parents or friends, we go to the theatre.

Another important way to make your writing more coherent is to always address the options in the same order. Notice that above I talked about watching movies at home, and then at the movie theatre. This prevents your audience from becoming confused.

So which method is the best?

That totally depends on your own ideas! In TOEFL or IELTS you won’t have much time to organize your ideas, especially in the speaking section (you can afford to take a little longer with your writing). There is no right answer; there’s only your answer. In the brief period you have to generate ideas, decide quickly which is the best method to answer the question. Talk about what’s true for you, develop your answer coherently no matter which method you choose, and just pretend you’re talking to a friend rather than a stranger or a microphone.