Writing

How do you write a good TOEFL Writing independent essay … good enough to get a score of 4 or 5? What I’ll do in this article is show you the process I use to write an essay, with a lot of tips along the way.

♥ ♥ ♥

Essentially, the independent writing task follows the organizational structure of what teachers call “the five-paragraph essay.” The five-paragraph essay consists of:

An introductory paragraph. This contains your thesis statement … your main idea, which you will elaborate on in subsequent paragraphs. Rather than a wordy, rambling introduction, aim for two or three clearly written sentences that accurately and succinctly describe your thesis. The goal of this paragraph is to communicate very clearly to your rater what you’re going to be writing about in the rest of your essay.

Three body paragraphs. Most independent writing tasks will ask you your opinion about a topic. It is preferable to have three main points. Each point should be expanded upon in its own paragraph. The first sentence in each paragraph should be your topic sentence; it will clearly state the main idea of this paragraph. The rest of the paragraph will provide support for that idea. I have more to say about those three points in this article.

A concluding paragraph. One or two sentences restating your thesis are sufficient.

♥ ♥ ♥

In the independent writing task, you are given the topic and the timer starts counting down: 30 minutes from start to finish. Here’s the topic (TPO 20):

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

Successful people try new things and take risks rather than only doing what they know how to do well.

Use specific reasons and examples to support your answer.

♥ ♥ ♥

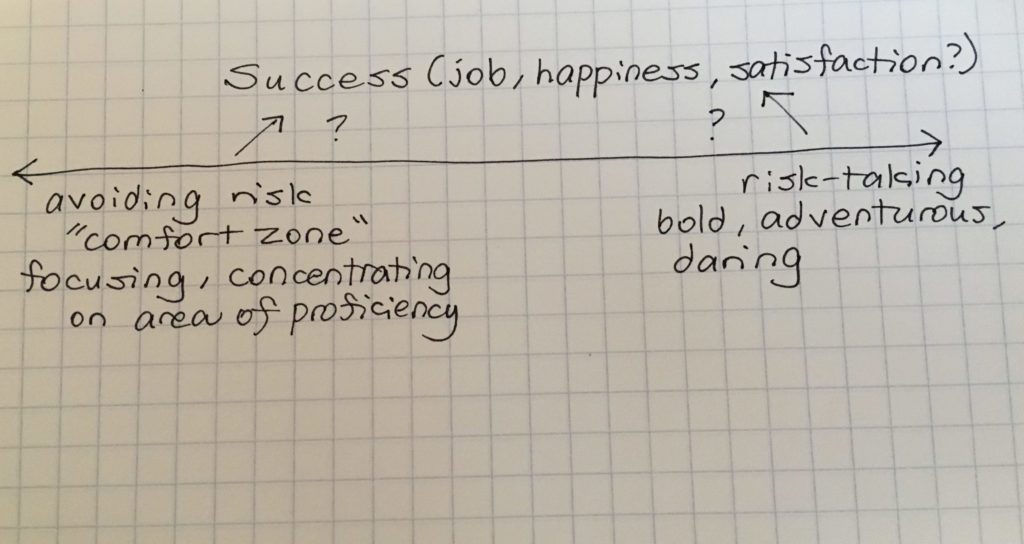

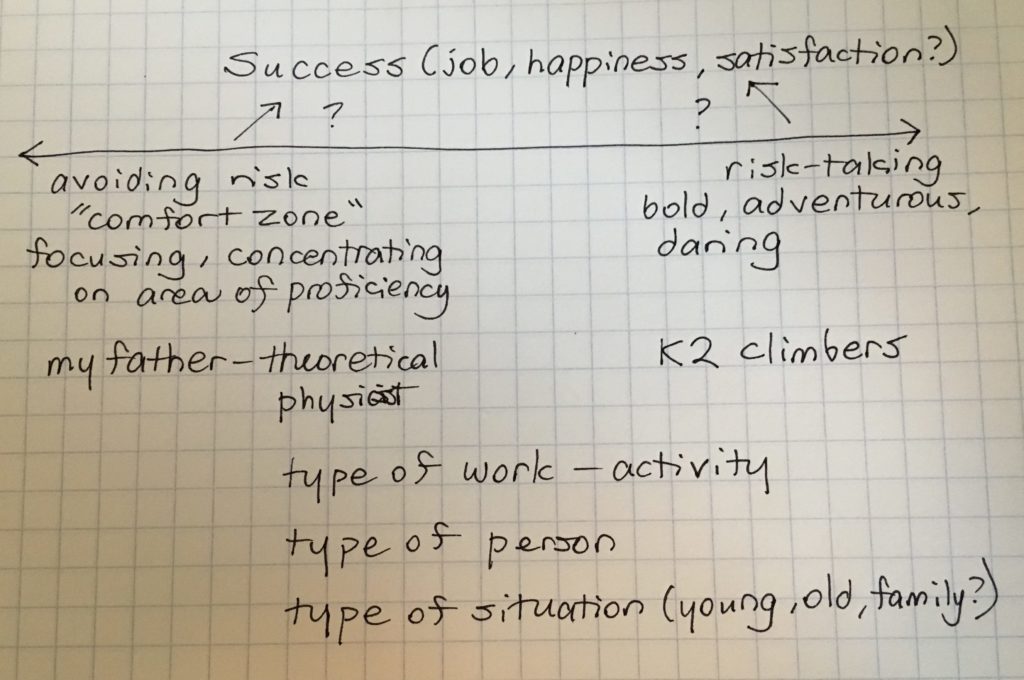

The first thing I do is to make sure I understand the question. It’s talking about what leads to success: risk-taking or sticking to what you do well. I might even illustrate this in my notes, which I’ll use before I start typing.

Notice that I’m already starting to accumulate some words or phrases that I may use in my essay.

TIP: Don’t start writing immediately! A few minutes to organize your ideas will pay off in multiple ways. Your essay will be clearer, more coherent, more focused, and easier for your rater to read.

♥ ♥ ♥

Now I need to develop a few ideas about the question: these will help me establish my stance – do I totally agree, completely disagree, or have mixed feelings?

TIP: It’s absolutely okay and often preferable to write an “it depends” essay. I have lots to say about this in this article. Unless you feel really strongly one way or the other, an “it depends” essay will reflect your own attitudes more accurately and, in my opinion, the most important objective in the whole essay-writing process is to say what you really think and believe.

♥ ♥ ♥

I finish up my written notes (what I would consider brainstorming) by jotting down a few preliminary ideas from my own experiences – an example of my father (not a risk-taker but a success in his profession) and some books I’ve been reading on risk-taking climbers who tried to ascend K2, the “savage mountain” in Pakistan. A bit of thought leads me to the conclusion that success comes a variety of ways, so it will depend on factors like the type of work or activity, the type of person, and maybe the type of situation the person is in.

TIP: My advice for TOEFL independent writing is the same as for independent speaking. Where do you find ideas and examples? From inside yourself. From your own experiences, your own viewpoints, your own examples. What’s really real for you is what you know best. From this reality will come the details and vocabulary you need to respond more effectively, no matter what you have to say.

♥ ♥ ♥

I’ve spent a few minutes thinking about the topic, gathering ideas, and figuring out my general approach. Now it’s time to start typing. But I don’t start off just typing the first thing that comes into my head. Instead, I type a bit of an outline, like this:

Thesis: Taking risks is sometimes necessary, but it’s not the only way to achieve success.

- To succeed in some types of work, you must focus on and master one particular thing. (father)

- Some types of work/situations are inherently risky, so people need to take risks to succeed. (climbing mountains, venture capitalism)

- The degree of risk you take depends on the type of person and the situation. (personality, age of person, family circumstances)

TIP: According to TOEFL Writing raters I have spoken to, it’s best to write five paragraphs: an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you aren’t a strong writer, those three body paragraphs may be fairly short. As long as your topic sentence is clear and you provide a few supporting details, in at least two subsequent sentences, you should be fine.

TIP: Having trouble coming up with three ideas? Think about how you might divide one idea in half. Maybe you are writing an essay supporting children wearing school uniforms and you can only come up with two points: 1) schoolchildren feel less peer pressure to be fashionable and 2) it’s easier for parents. Maybe you could divide the second point in half. One new point is that parents save money. Another new point is that parents will waste less time getting kids ready for school in the morning. Now you have three different points for your essay.

TIP: Take the time and make the effort to organize your ideas and structure your essay before you start writing. Never start writing without knowing what you’re going to say! The most important thing you can do is to make your essay easy for your rater to read and understand. Lots of words on the paper without a clear, coherent structure behind them is going to give your rater a headache and they, in turn, will give you a lower score.

♥ ♥ ♥

Here’s my finished essay.

Great adventure stories always feature heroes and heroines who are bold, daring, and fearless. Taking risks is inherent to the drama, and that’s what makes the story so compelling. However, while risk-taking may sometimes be praiseworthy and even necessary to succeed, I believe there are many times when it’s preferable to avoid risks, stay in one’s comfort zone, and achieve success without going to extremes.

First of all, many jobs require focus and concentration on one area of expertise, rather than risk-taking and trying new things. Work that is highly specialized and technical may be so difficult that success only results when people remain in their particular area of proficiency. For example, my father, a theoretical physicist, spent virtually years and years exploring just a few extremely complex and challenging problems that no scientists had yet solved.

On the other hand, some jobs, activities, or situations are inherently dangerous and cannot be completed successfully without people taking risks. These risks may be physical; mountain climbers trying to ascend Mount Everest or K2, for example, know that despite careful planning and extensive physical training, they will encounter many dangers during these pursuits. Or the risks may be monetary. Few stockbrokers or venture capitalists achieve financial success without taking risks with their investments.

All in all, whether it’s better to take risks or play it safe really depends on a person’s individual characteristics and their situation. While some people thrive on taking risks, others prefer to focus on activities and tasks that they feel comfortable doing. Both types of people are equally capable of becoming successful in their jobs or personal lives. Furthermore, as people’s circumstances change, they may feel like taking more or less risks. Young adults tend to feel more adventurous, for example, while married couples with young children may opt for more security.

So although we may enjoy reading stories about great risk-takers and adventurers, explorers and visionaries, in real life, most of us recognize that for many people and in many situations, there’s nothing wrong with sticking to the known and familiar. However we define success, whether in our jobs or the pursuit of happiness, there are many roads to its accomplishment.

♥ ♥ ♥

TIP: Many students are told that, in their introduction, they should start with a “global,” very broad statement and include all the possible choices from the topic. An example from one of my students:

People will set up different goals for new year’s resolutions. Some people consider their health as the most important task in their life, while others put time management in the first place. In my opinion, I will choose to help others in my community to be my new year’s resolution.

This is not my preference. In this essay, I chose to talk about literature that features risk-taking because I had just finished reading a book about climbing K2, the most dangerous mountain in the world. But I might also have started with a briefer introduction, for example:

Being bold and adventurous, taking risks and trying new challenges may certainly but not always lead to success. However, I believe there are many times when it’s preferable to avoid risks, stay in one’s comfort zone, and achieve one’s life goals without going to extremes.

I have two main goals in my introduction. The first, which is mandatory, is to make sure the reader understands my thesis and what I’m going to talk about in the rest of the essay. The second, which is optional but definitely preferable, is to make the reader interested in what I’m going to say. Imagine a rater reading essay after essay after essay. Do you want their eyes to glaze over or do you want to capture their attention? A good writer always aims for the second reaction.

TIP: Students are also often told that they should avoid using the first person, “I.” I disagree. If you are asked your opinion, it’s natural to use “I.” But when you use different persons (first, second, and third) in your writing, be sure that you make conscious, careful decisions about which to use. Notice that in my essay, I generally stick with the third-person, but occasionally switch to the first (I and we). Be careful not to switch randomly, especially between the second and third person. An example of what to avoid:

Students should be allowed to choose what type of room they want to live in at college. You might find it enjoyable to have a roommate, but some students like living alone. Independence is usually important when you go to college, so students should be allowed to live in a single room if they want.

TIP: Long essays are not necessarily better essays. Although less fluent writers will find it impossible to produce a lengthy essay, length alone will not necessarily guarantee a high score. My essay is 364 words, far fewer than some of my students’ work. I wrote fewer words, but I took more time organizing my ideas in the beginning, choosing my words and structures with care, and proofreading my work at the end. I recommend that you do the same. And although I once had a student whose teacher recommended initially writing about 500 words and then paring them down to about 400, I definitely don’t use that approach. I think it’s far better to spend your time organizing your ideas and carefully crafting your sentences so they don’t need to be deleted or extensively rewritten.

TIP: Keep your conclusion short and sweet. Go back to your introduction. Rephrase it and, if possible, recapture the idea that (hopefully) intrigued your reader in the beginning. For example, in my conclusion, I reiterated the idea of adventure stories.

TIP: Don’t feel that you need to write your essay “in order.” After I write down my thesis statement and the topics of my three body paragraphs, I often skip the introduction and go to the first body paragraph. It’s sometimes easier to introduce the essay when I already know what I’ve said in its body.

TIP: Always save time at the end to proofread your work. So many students’ essays that I read suffer from unnecessary language use problems (subject/verb disagreement, improper tense, incomplete sentences), punctuation mistakes, weak vocabulary or word form errors, and misspelling. I say “unnecessary” because the students, when they reread their work, recognize the errors without my pointing them out. Although your essay doesn’t have to be perfect to get a top score, you want to avoid as many of these mistakes as you can. Far better to keep your essay on the shorter side, and leave enough time to make as many corrections as you can in the last five minutes. Reading your essay aloud (in your head) may help you to identify these mistakes more easily. Error correction is also a useful skill that you can work on when practicing by yourself.

TIP: Each of your main points needs to be developed and elaborated upon. This is the “meat” of your essay, and it’s what raters will focus on. Avoid using vague reasons (“I will learn more knowledge”), unsubstantiated information (“research shows” or “the Dalai Lama says”), or trite and over-used expressions (“enhance my social skills” or “broaden my horizons”). It is much better to support your reasons with personal and authentic examples. Raters can usually tell when you are making up a story about yourself or “my friend Kenny.” Good English writing has its own “voice” … it’s genuine, not fake; individual, not generic; specific, not vague.

In an earlier post, I talked about some strategies to use when asked for your opinion, especially in a test like TOEFL or IELTS. I’d like to elaborate on this topic, with many thanks to my long-time student Sam who spent a lot of time discussing these ideas with me.

Let’s say you’re given the following question:

Some people prefer to watch movies or films at a cinema or movie theatre. Others prefer to watch them at home. Which do you prefer and why?

So now what do you do?

First of all, many students ask me how they can generate ideas, especially when they have a very short time to prepare an answer. My most important piece of advice is to answer truthfully. If you say what you really think, all those ideas will be in your head already. And your response will sound more real, more genuine, and more personal … it won’t sound like everyone else’s.

Once you have some ideas, how do you present them? There are three different strategies you can choose.

The 100% Method

With this method, you choose one side and all the content in your answer supports that choice. Many people think you need two reasons in a 45-second response, but this simply isn’t true. You can provide one good, well-developed reason or multiple reasons … whatever comes into your mind that you’re able to talk about. A 100% answer might sound like this:

Well, I think I’d rather watch movies at home because I’m a parent of small children and we don’t have a lot of extra money for a babysitter. So a couple of nights a week, my husband and I will make sure that the kids get to bed on time and then we’ll curl up on the couch and watch a movie on Netflix. We can pop some popcorn and relax and if one of the kids wakes up we can pause the movie and take care of the situation and then go back to the movie. And if we get really tired, we can stop the movie and just finish it the next evening.

The 100% Method is also frequently used when answering an essay question such as the TOEFL independent writing task. Most test-takers choose one option or the other and then focus on three reasons (one per paragraph) supporting that choice. But as you’ll see below, although this is the most common method, it’s not the only way to write this kind of essay; and you’ll probably impress your rater if you opt for another method that’s not quite so typical.

The 90/10 Method

With the 90/10 Method, you spend 90% of your time talking about the option that you choose, but you also acknowledge the other choice. This is a good method to use if there are certain reasons or circumstances when you might prefer the other option, but you don’t want to spend too much time talking about them. A 90/10 answer could go as follows:

You know, on special occasions when I’m going out with my whole family, it’s fun to watch a movie in the movie theatre. But most of the time, I watch movies at home. It’s just easier and more relaxing. I don’t have to pay a lot of money on tickets and parking, and I don’t have to spend time travelling to the movie theatre … because where I live, the nearest movie theatre is 10 miles away. And I have more choices, because at our movie theatre, they only play one movie each week, and maybe it’s not a movie I’m interested in. If I stream a movie on my computer, I can watch pretty much anything I want.

You can also use this same method if you decide to spend most of your time talking about the option you wouldn’t choose (and this is a perfectly acceptable way to answer this type of question). So, for example:

I don’t mind watching movies at home, but I really never go to the movie theatre. Actually, I haven’t gone to a movie at the movie theatre for years. It seems like if I go during the daytime, I always get a headache when I come back out of the dark theatre into the daylight. And movies at night definitely don’t work for me because I go to bed really early. I guess I also spend a lot of time worrying about whether the tickets will be sold out and then, when I’m seated, if someone is going to sit in front of me and block my view. I just find going to the theatre kind of stressful and unpleasant, I guess.

One thing to note is that the 90/10 Method is often used when we’re writing a persuasive or argumentative or opinion essay (as is often the case in TOEFL or IELTS). This type of writing is usually more convincing (and therefore “better”) when we present an opposing argument and then proceed to counter it with our own opinion. Each paragraph will always focus on your own beliefs, but you’ll acknowledge the “other side.” For example, an essay for the TOEFL independent writing task might be organized as follows:

Opening Paragraph Thesis Statement: Although there are reasons why people might like movies in the movie theatre, I prefer to watch them at home.

Body Paragraph 1: Sometimes discount tickets are available, but movies at home are usually cheaper. The paragraph then elaborates on the savings you get (not paying for tickets, parking, transportation, babysitting, food when watching the movie, etc.)

Body Paragraph 2: On special occasions it’s fun to go to the theatre, but it’s a lot more convenient for me to watch movies at home. You then cite several conveniences (can be a last-minute decision, more comfortable surroundings, no travel to and from theatre).

Body Paragraph 3: If you live in a big city you might be able to see a wide variety of movies, but I don’t have that option where I live. You describe how your movie theatre selections are limited while you have tons of options (use some specific examples) at home.

The 50/50 Method

With this method, you spend half your time talking about one option and half the time talking about the other. You can also call this the “it depends” method.

To ensure coherence and focus in your answer (especially if you have a very limited time), it’s essential to center your response around ONE factor only. What does your choice depend on? Make that clear in your answer. Here’s an example:

Well, whether I watch a movie at home or in a theatre really depends on whether it’s a weekday or weekend. When I have to go to work the next day, I can’t stay out too late and I also don’t have enough time to travel to and from the movie theatre. So on a weekday, my wife and I really like to put the kids to bed early and snuggle up on the couch to watch Netflix. On the other hand, on a Friday or Saturday night, we’ll get a babysitter and have a special date night. One of our favorite things to do is to have dinner and then go see a film.

This method is equally effective in a written essay, as long as you organize your answer carefully in the beginning and make sure you follow the right structure. To expand, just think of more factors that your choice depends on. For example:

Opening Paragraph Thesis Statement: Whether I watch a movie at home or in the movie theatre depends on several factors.

Body Paragraph 1: Time of the week. Weekdays I stay at home. Weekends I go to the theatre.

Body Paragraph 2: Type of movie. I like to watch romantic and/or sad movies at home (embarrassing to watch love scenes with strangers, I cry easily). I like to watch action movies in the theatre (special effects, surround sound, sharing the audience’s excitement).

Body Paragraph 3: Who I’m with. When I’m alone, I watch movies at home (I don’t like to go out by myself, feel uncomfortable being by myself in a theatre). When I’m with my parents or friends, we go to the theatre.

Another important way to make your writing more coherent is to always address the options in the same order. Notice that above I talked about watching movies at home, and then at the movie theatre. This prevents your audience from becoming confused.

So which method is the best?

That totally depends on your own ideas! In TOEFL or IELTS you won’t have much time to organize your ideas, especially in the speaking section (you can afford to take a little longer with your writing). There is no right answer; there’s only your answer. In the brief period you have to generate ideas, decide quickly which is the best method to answer the question. Talk about what’s true for you, develop your answer coherently no matter which method you choose, and just pretend you’re talking to a friend rather than a stranger or a microphone.

In my last post, I talked about how the known-new contract can help your writing to flow … to be more coherent and cohesive. Remember, the basic idea is that you present known information in the subject, and introduce your new information in the predicate. Below, I’ll describe three practical ways you can put this into practice. For the first two methods, I’ll give diagrams where A is the original subject and B, C, and D are the predicates.

Constant subject model

With the constant subject model, your subject (A) stays the same in every sentence. The pattern goes like this:

A > B (one new thing about A)

A > C (a second new thing about A)

A > D (a third new thing about A)

To prevent boring your reader, you can rephrase your subject (put it in different words) or use a pronoun. Here’s an example:

Phrasal verbs are a challenge for English learners. These phrases consist of a common verb and a word known as a particle. Phrasal verbs include very idiomatic expressions such as “to hang out” or “to drop by.” Usually, these constructions replace other, more formal words in English. Phrasal verbs must be mastered if learners want to improve their fluency.

Notice that although the subject (phrasal verbs) stays the same, I vary the wording of the subject while still retaining clarity. The reader should know that I’m still talking about phrasal verbs in every sentence.

Derived model

With this model, you begin with subject A in your first sentence. You present new information about the subject in the predicate. Then, in subsequent sentences, your subject becomes a “subset” of A, and you include new information in the predicate. In other words, you break your subject up into different parts or facets, and present new information about each.

A > B (new information about A)

Subset of A > C (new information about a part of A)

Another subset of A > D (new information about a part of A)

The derived model would result in something like this:

Phrasal verbs are a challenge for English learners. The first part of the phrasal verb is the verb, which is usually quite common. The second part of the phrasal verb is the particle, which can easily be confused with a preposition. The combination of the two parts forms the phrase, which speakers often use in idiomatic speech. Examples of common phrasal verbs include the idiomatic expressions, “to hang out” and “to drop by.”

Notice that, after the first sentence, each subject is something related to phrasal verbs. And I present new information about this subject without (I hope) confusing the reader.

Chained model

With the chained model, you form a sequence or chain in your writing. You start with a given subject (A) and include new information in the predicate (B). In the following sentence, the idea in the predicate becomes your subject (B), and you add more information in the predicate (C). And so on, and so forth.

A > B

B > C

C > D

Here’s an example:

Phrasal verbs are a challenge for English learners. The challenge comes because the meanings of these words are difficult to guess. Often, the meaning of the phrasal verb can be quite different from what the learner might expect. For example, a learner might hear the phrasal verb “to hang out” and think it has something to do with hanging laundry outside. But, in fact, “to hang out” is just another way of saying “to be with friends.” This idea of “being with friends” might also be expressed with a more formal English word, such as “to socialize.” But these formal words are less likely to be used in casual speech.

See how I’ve taken the main idea from the predicate of the preceding sentence and made it the subject of the subsequent sentence? When this method works right, the writing will really flow naturally and carry the reader effortlessly along for the ride. Just be careful that the ride doesn’t go on for too long! If you reach sentence G or H, you may have drifted quite far from the original subject of A.

What’s important to realize is that you don’t need to use just one of these methods. In fact, you shouldn’t. Good writing includes a combination of all three. Think about your material and what you want to say. Organize your ideas in a logical progression. Then consider what method is going to work best for each part.

Coherence and cohesion are two terms we use to describe good writing (and speaking). Coherence means that ideas are linked together in a logical order; while cohesion can be thought of as the unity that results when these links are deliberately made through certain techniques, such as repeating words or phrases.

Basically, coherent and cohesive writing flows. It’s not choppy. One idea just naturally progresses to another idea. Readers move through the text effortlessly. It’s all smooth sailing, from the first word to the last.

How do we achieve this magical feat?

Linguists often talk about something called the known-new contract. While this is a bit complicated, it boils down to helping out your reader by ordering your information so that known material is given before new material. Look at these two groups of sentences:

I.

Phrasal verbs are verb phrases formed from a verb and a particle. Discourse markers differ from phrasal verbs since they are formed from only one word. Transitive verbs have direct objects, while intransitive verbs don’t. Phrasal verbs can have direct objects, but they may also be intransitive. The particles in phrasal verbs may or may not have direct objects.

II.

Phrasal verbs are verb phrases formed from a verb and a particle. Particles may look like prepositions, but they actually aren’t the same. Unlike prepositions, particles don’t need to have an object. So, for example, in the phrasal verb, to hang out, out looks like a preposition, but it has no object. Therefore, it’s not a preposition. Particles may have objects, but unlike prepositions, they don’t have to have them.

Do you see how difficult the first group is to read? The subject of each sentence is different, and the sentences don’t flow. Each sentence provides you with new information that doesn’t relate to the preceding sentence.

On the other hand, in the second group, the ideas flow from sentence to sentence. It starts with the given information, a definition of phrasal verbs. But since the writer assumes the information about particles is new, she then moves on to define particles by comparing them to prepositions.

Obviously, determining what is “known” to your reader is important. In the writing above, I assumed that my reader would know the different parts of speech in English. If I were writing for beginners in English, I would start with more basic information. But whoever your audience is, the principle remains the same. Start with known information; then introduce new information. This helps make your writing coherent and cohesive … something your reader will definitely appreciate.

In my next post, I’ll talk about three simple ways to organize your written sentences following the known-new contract.

When I was in elementary school, many students learned to diagram sentences in English class. Not everyone enjoyed this. But I think the reason was not because of the method itself, but because of the way we were taught. Teachers would give us a sentence to diagram and make us stand up in the front of the class and write it on the blackboard. If we made a mistake, everyone would laugh at us … or so we feared.

In fact, I believe that the practice of diagramming sentences is not only fun, but also very useful. Diagramming taught me how English grammar works “in real life.” As a result, I became a much better writer. And when I taught my children at home, I made sure that they learned how to diagram sentences as well.

Diagramming helps students learn the different parts of speech. What is a noun, and a noun phrase? What is a preposition, and what is its object? What are verbs and what are adverbs? Diagramming trains you to identify these rapidly. It also teaches you how the same word can fulfill different functions … an important concept in English, where we have so many words that can be used for several parts of speech.

When you diagram, you have to identify the subject, the predicate, and how the different parts of the sentence fit together. It becomes much easier to construct grammatically correct sentences when you see how the whole sentence works together.

English learners particularly benefit from diagramming when their own language follows very different grammatical structures.

Diagramming isn’t for everyone. It isn’t for beginning learners. You need to have a solid understanding of basic English before you start. It isn’t for people who just want to speak and understand spoken English. Diagramming really focuses on written English … and spoken English often follows quite different grammatical patterns than written English.

I think diagramming works best for students who need to improve their writing skills, either for academic or business purposes. It also seems to appeal to people who have a logical, analytical turn of mind. For example, when I taught diagramming in class, the student who made the quickest progress and enjoyed it the most was a high school mathematics teacher.

You can find many resources for studying diagramming on the internet. However, I think that it really helps to work with a teacher, especially as you learn to diagram more complex sentences. Not every teacher knows how to diagram, and not every teacher believes it’s an effective method. But it’s definitely worth discussing this with your teacher, or seeking out a teacher who teaches it. See for yourself whether diagramming helps you master the challenges of English grammar.