Words we use for words

I am not a linguist (a person who studies languages).

But during my English lessons, my students and I often discuss what “kind” of English they want to learn. Colloquial? Informal? Idiomatic? Slang? Dialect? What do all those terms actually mean?

In this article, I will try to explain what we English teachers mean when we throw these terms around. As I said, I’m not a linguist, so please take my information “with a grain of salt.”

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Register. Basically, linguists use register to define a language’s degree of formality. In academic writing and social situations such as job interviews and committee meetings, people tend to use formal register: higher-level vocabulary words and less slang, with more attention to proper grammar and precise wording. On the other hand, casual or informal register is more conversational, more colloquial, more idiomatic, and more “natural.” In general, English writing is more formal in register, speaking is less so. But for both, there’s still lots of variation between formal and casual register, and English learners need to pay attention to identifying which people and situations require what degree of register.

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Vernacular. This is a broad, rather “catch-all” phrase used to describe “the language of a people or a national language.” The term can also be used as a synonym for colloquial or informal. It includes both spoken and written English.

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Colloquialism. Colloquial. In contrast to formal language, colloquialism (general parlance) is simply the everyday language people use when they are casual, relaxed, and not trying to impress people. This general term includes slang, abbreviations (like LOL), and idioms. When English learners want to sound “real,” native-like, and authentic, they want to learn this kind of English. Colloquialism is more common in spoken English, although written texts that try to replicate human speech often use colloquial expressions. Colloquial language can generally be understood by people of different ages and socioeconomic classes in a broad geographical area, but some expressions are more limited.

For example, many Americans, when they tell someone that they’re going out for a drink with a friend, might say, “We’re gonna go grab a …” “Gonna” is a widely used colloquialism for “going to.” Your English textbook may tell you that Americans say, “I am going to walk to the store.” In fact, nine times out of ten, you will hear them say, “I’m gonna walk to the store.’ And although “to grab” generally means to catch or seize something, Americans will understand that this simply means to go get something right away, and relatively quickly. However, in different regions, the name for that drink may vary. For example, in the Northeast, people usually say a “soda,” in the South, a “Coke” (even when the drink is a different brand), and in the Midwest, a “pop.” So, there are colloquialisms that are more generally used throughout the US, and others that are more regional.

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Idiom. Idiomatic. I have already written two articles on idioms so I won’t repeat myself too much here; my general definition is:

- They are a group (or pair) of words in a specific order that doesn’t change. The speaker will include the idiom as one fixed “chunk” of language into their speech or text.

- Their meaning is different from the individual words that form the phrase. In other words, you won’t be able to figure out the meaning of the idiom from the meaning of the individual words.

- They are usually specific to a certain language and can’t be translated word-by-word to another language.

While colloquialisms include any informal, everyday expressions, idioms are limited to those phrases that are both fixed and figurative. Most idioms are colloquial; we wouldn’t use them in formal speech, but not all colloquial language is idiomatic

Remember … fixed and figurative. The word order will generally stay the same, and a literal (word-for-word) meaning won’t help you catch the meaning, although it can result in some funny images. If your children are “glued to the TV set,” they aren’t (fortunately!) literally and physically attached to the screen. If you take my advice with “a grain of salt,” you aren’t going to be eating salt … you’re just going to be a little skeptical. If you’re “beating a dead horse,” you’re not committing animal cruelty … you’re simply wasting your time on something that’s already over and done with.

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Slang. Slang is casual spoken language that’s very informal. While colloquialisms can be understood by most Americans, slang is specific to a particular group, age, region, or profession. Slang can become a group identity … so that if you know the slang, you “belong” to the group; if not, you’re an outsider. Slang generally goes in and out of fashion. Words like groovy and sweet (to describe something pleasing) now seem very outdated. Some slang expressions are perfectly acceptable in any conversation (cool or brilliant or yikes). Others are more vulgar (offensive and rude) and should be used with caution! Urban Dictionary is a wonderful resource for learning American slang (but it’s definitely X-rated, so readers beware!).

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Jargon. Jargon is a language that’s specific to a particular activity or profession. Lawyers use legal jargon (appeal, motion, bench); golfers use golf jargon (birdie, boogey, par).

♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠ ♠

Dialect. Dialect is a particular form of a language spoken by a certain group of people, such as southern English, Black English, even standard English. When it’s in the form of writing that shows the accent and way people talk in a particular region, dialect can be a huge obstacle for readers of English literature. Here are some examples:

Dialect in Huckleberry Finn (Mark Twain):

Jim (a Black man in what the author describes as “Missouri negro dialect”): I didn’ know dey was so many un um. I hain’t hearn ‘bout non un um, skasely, but old Sollermun, onless you counts dem kings dat’s in a pack er k’yards. How much do a king git?

In Standard American English: I didn’t know there were so many of them. I have scarcely heard of any of them, except old Solomon, unless you count the kings that are in a pack of cards. How much does a king earn?

Dialect in The Secret Garden (Frances Hodgson Burnett):

Dickon (a country boy in Yorkshire, England): It’s rare good for thee. There’s naught as nice as th’ smell o’ fresh growin’ things when th’ rain falls on ‘em. I get out on th’ moor many a day when it’s rainin’ an’ I lie under a bush an’ listen to th’ soft swish o’ drops on th’ heather an’ I just sniff an’ sniff … I never ketched cold since I was born. I wasn’t brought up nesh enough.

In Standard American English: It’s really good for you. There’s nothing as nice as the smell of freshly growing things when the rain falls on them. I get out on the moor many days when it’s raining and lie under a bush and listen to the soft swish of drops on the heather and I just sniff and sniff … I’ve never caught a cold since I was born. I wasn’t brought up nicely enough.

Although literature written in dialect closely mirrors the speech patterns of the characters and thus makes them sound more genuine, it can be exceedingly difficult for even native English speakers to read. In the same way, a movie in which actors speak dialect can be almost inaccessible. If this happens to you, try not to feel frustrated! Many American high schoolers have given up (or wanted to) on Huckleberry Finn, even though it’s considered a classic in American literature.

Building a five-paragraph essay

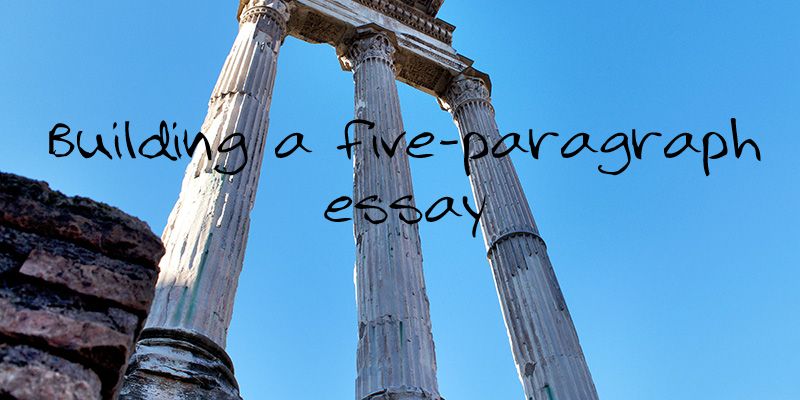

The “classic” five-paragraph essay consists of several parts: the introduction, three body paragraphs, and the conclusion. This format should be used in the TOEFL independent essay as I describe in this article. Although your academic work will probably be longer than five paragraphs, essays like this give you excellent practice in organizing your ideas and perfecting your writing style. Think of them as the scales that pianists run through many times before tackling a more challenging piece of music.

You might think of your essay as a classic Roman construction … like this facade of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in Rome, Italy. Given that it was built over 2,500 years ago, it certainly has a solid structure! Your essay should have the same.

Let’s discuss the elements in your well-built essay and then we’ll look at more specific details on its construction in the following article [to be written].

First, you need a solid foundation.

Your introduction lays the foundation of your essay. And to set a foundation, you must have, at the very center, a thesis. The thesis sums up your central idea; everything built on top of it, your three body paragraphs and your conclusion, must rest on it, must be attached and connected.

One of the biggest problems my writing students encounter stems from not beginning with this foundation stone. They begin writing their essay with a vague idea of what they’re going to say, and jump from point to point so that nothing connects to a center. If your essay structure is not built solidly on a central thesis, the essay will fall apart. It will lack coherence and cohesion, which are essential to a good essay.

When I read essays like this, I ask my students to tell me what their thesis is. In one sentence, what is this essay saying? If they can’t do this, then we know that there’s a problem with the thesis; and with a shaky, wobbly foundation, it can never stand on its own.

Let’s also consider what your foundation looks like to the outsider, the reader. Is it inviting … does the reader want to enter your essay and see what’s inside? Or is the foundation boring, overly general, uninviting? An attractive “hook” to interest the reader and a clearly stated thesis statement are like a set of wide, shallow stairs that help usher the reader into your essay.

Next, you need three strong columns in the form of three body paragraphs. Each column rests on the foundation, your thesis. If a column is resting outside the foundation, dangling in space so to speak, the essay is going to fall apart or, at the very least, seem unbalanced and poorly constructed.

Although your columns, your paragraphs, aren’t going to look exactly the same … each will be expressing a different point … they should have a sense of being coordinated and similar. For example, you won’t have one paragraph twice as big as the other two. You won’t start two paragraphs with a topic sentence, and then end the third with the topic sentence. Your three body paragraphs, like three visually pleasing columns, will give your reader a sense of logical order and well-planned structure.

Finally, you cap off your essay with a conclusion. Notice that the Temple of Castor and Pollux has a rather ornate top that embellishes the whole construction. Your conclusion doesn’t need to be so fancy! You mainly need to focus on constructing a conclusion that reflects the ideas and style of the introduction. Just like you wouldn’t place a thatched roof on top of a Roman temple, you don’t want a conclusion that introduces completely new elements or distracts from the rest of the essay. Like the foundation, the roof should be well connected to the three columns. The ideas expressed in your conclusion should rest solidly on the material in your three body paragraphs.

In the next article, we’ll discuss some ways to build a real five-paragraph essay, putting all these elements into practice.

Using reporting verbs

In my previous article on reporting verbs, I discussed a number of different verbs that you can use to describe what something or someone says or thinks.

Now I’d like to talk about the grammar you should use for reporting verbs.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

There are two basic models used with reporting verbs. Some reporting verbs follow one model, some reporting verbs follow another, and some can follow both.

The first model is verb + noun (or noun phrase). For example:

The author affirms the existence of life on the sea floor.

The text discusses the possibility of life on Mars.

The lecturer proposes alternative theories to those stated in the text.

The second model is verb + that + clause (subject/verb)

The author observes that many animals have evolved to adapt to the extreme environment.

The text states that no life could exist on Mars.

The lecturer suggests that other theories might better explain this phenomenon.

As a writer, you will need to know whether each reporting verb you use follows the first model, the second model, or both.

First model only:

The author refutes the theory that life exists on Mars.

NEVER: The author refutes that life exists on Mars.

Second model only:

The lecturer concludes that several theories are equally valid.

NEVER: The lecturer concludes the equal validity of several theories.

Fortunately, most reporting verbs can follow both models:

First model: The researchers acknowledge the lack of convincing data yielded by recent studies.

Second model: The researchers acknowledge that recent studies have yielded little convincing data.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

The second issue regards tense. For relatively simple tasks like the TOEFL integrated essay, I would ALWAYS recommend using the simple present tense for your reporting verbs. This is especially true if the reporting verb is followed by a clause describing something that happened in the past.

For example, this is a relatively easy sentence to write with the reporting verbs in the simple present tense. Note the verbs in the subsequent clauses.

The professor points out that the use of toxic chemicals in the 1960s damaged vegetation and caused many animal species to disappear. She notes that many fertilizers were used without knowledge of their harmful effects.

But if we put the reporting verbs in the simple past tense and want to stay consistent in our use of tense in the subsequent clauses, we have to write:

The professor pointed out that the use of toxic chemicals in the 1960s had damaged vegetation and had caused many animal species to disappear. She noted that many fertilizers had been used without knowledge of their harmful effects.

Or in another example:

Simple present: The professor states that the fire gave new opportunities for small animals and actually strengthened the food chain.

Simple past: The professor stated that the fire had given new opportunities for small animals and had actually strengthened the food chain.

Finally, if you are stating general facts and not referring to previous events or situations, I suggest you keep everything in the simple present tense.

The professor rejects the belief that dogs are more intelligent than cats. She points out that most research studies are deeply flawed. Pointing out that cats are more independent and less willing to please than dogs, she believes that cats are equally capable of performing tasks that researchers present to them.

Why language learning is like working out

As someone who’s worked out almost every day for the past 20 years, I think a lot about exercise. And it seems to me that the advice I give to language learners is a lot like that I give to people who are trying to get in better physical shape. (Yes, that’s me in the photo above, after a workout while on vacation … I literally never take a break from exercise because “if you don’t use it, you lose it,” and that goes for fluency as well!) So what do I tell people? First …

You need to find something to motivate you

When people decide to lead a fitter lifestyle, they usually have something that inspires them to begin … whether it’s a warning from their doctor, the desire to keep up with their kids, or simply a good long look in the mirror. Language learners should find something that motivates them as well. Maybe it’s a TOEFL score that will be your ticket to a prestigious university or a better job. Maybe it’s an opportunity to live in an English-speaking country. Maybe it’s just a deep-seated desire to speak English better. Whatever it is, keep this motivation in mind because …

You need to accept that this is a long-term endeavor

You don’t become fit overnight, and you won’t learn better English overnight either. Furthermore, just like exercising, you need to keep at it to stay at whatever level you’ve achieved. There are no magic potions or shortcuts to attaining fitness or fluency. You have to make up your mind to stick with it over the long haul. In this case …

You probably need someone to help you

When you’re developing a fitness routine, you may choose to use a personal trainer or enroll in exercise classes. When you’re developing fluency, you may want to find a teacher or an English class. But if these don’t suit your personality or your circumstances, think outside the box. When I started exercising, I became very active on an online forum for people who work out at home. You may be able to find an online community of English learners, or just one learning partner. The goal here is to find an individual or a community who can help answer questions, give you advice, sympathize with your struggles, and provide motivation and support. Language learning is more fun when you make connections, which brings me to another piece of advice …

You should pick language learning activities you enjoy and that suit your learning style

I would never have continued working out for so long if I weren’t doing workouts I enjoyed. When I started 20 years ago, I was homeschooling my three children and couldn’t get to a gym regularly. Well, home workouts turned out to be perfect for me, and I still look forward to my morning exercise routine every single day. If you don’t enjoy what you’re doing, it’s going to be hard to keep doing it for any length of time. There are soooo many options for learning English, even for (relatively) boring stuff like grammar. Sure, you can get a grammar textbook, but you can also study with a teacher, or go to my favorite grammar website, or listen to YouTube videos or other online materials. And when it comes to reading and listening, the sky’s the limit! However, while you definitely need to choose activities you enjoy, you also need to realize that …

You have to push yourself to make progress

Language learning, like exercising, isn’t all fun and games. I absolutely love my workouts, but they’re hard work! At the end of a cardio session, I’m usually dripping sweat. When it comes to weight lifting, that last repetition is a killer! Same with language learning. Stephen Krashen, one of the biggest names in second language acquisition, theorizes that learners acquire language through input + 1. Input is the stuff coming in … whether it’s an episode of your favorite English series, a podcast, or a news article. +1 means that it’s just a little bit more advanced than your current level. It’s the same principle with fitness. If I always do bicep curls with a 10-pound dumbbell, when it no longer challenges me, my muscles won’t get any stronger. If I switch to 12-pound dumbbells, I’ll continue making progress. Same thing with language learning. You always need to be pushing yourself a little bit … not too hard or you might get discouraged, not so challenging that it’s no longer fun, but hard enough so that you keep getting better. You can speak a bit more confidently, you can understand more of what you hear, you can read more challenging material, you can write more quickly, with fewer mistakes. With a bit of effort, made consistently, you’ll be amazed at what you can achieve!

Two languages

This may be a discouraging thought but the fact is, when you learn English (or most other languages), you’re dealing with not one but two languages … spoken English and written English.

In his lectures on the history of human language, Professor John McWhorter points out a couple of striking differences between spoken and written English:

- Spoken English uses a much more limited vocabulary than written English. First, there are the “big” words that you are likely to encounter only in written English, and often in more formal or academic writing. Even native English speakers may have to look these up in a dictionary: words like adumbrate, derisory, and hyperbolic. English speakers will rarely use these in speech and, if they do, they will tend to sound a bit pretentious (like they’re trying to show off and impress people). But spoken English also limits more ordinary words; for example, we are likely to use a lot of rather than numerous, a great many, or a multitude of.

- Spoken English has no punctuation. In spoken English, we don’t worry about whether we’re using complete or incomplete sentences; there are, in fact, no sentences. Instead, English speakers tend to put together “word packets” that, if written down, would not necessarily follow the rules of syntax that are expected in written English. Spoken English also uses shorter and simpler structures than written English. Professor McWhorter gives an example of this in a transcription of an academic conversation:

On a tree. Carbon isn’t going to do much for a tree really. Really. The only thing it can do is collect moisture. Which may be good for it. In other words in the desert you have the carbon granules which would absorb, collect moisture on top of them. Yeah. It doesn’t help the tree but it protects, keeps the moisture in. Uh huh. Because then it just soaks up moisture. It works by the water molecules adhere to the carbon moleh, molecules that are in the ashes. It holds it on. And the plant takes it away from there.

I have students who prepare for tests of speaking ability by writing down transcripts of what they want to say. But this hardly ever sounds natural. Here’s an example of a prepared, written response to a typical TOEFL question compared to a natural, spoken one:

Question: Some students prefer to work on class assignments by themselves. Others believe it is better to work in a group. Which do you prefer? Explain why.

“Prepared” written response:

Considering various aspects of this situation, I believe that it’s preferable for me to work on class assignments by myself. This is due to the fact that I’m a fairly solitary individual who profits more by working in isolation and by concentrating and focusing more fully and deeply on my assignments. As a true introvert, I feel more anxious and apprehensive when I have to interact with my peer group. Therefore, I believe that engaging in various academic tasks by myself results in a better performance and hence higher grades.

Natural spoken response:

Well, I guess I’d rather work by myself on my class assignments. I don’t know … I guess I’m kind of an introvert … I’m used to working by myself … you know, I listen to music and sort of tune out what’s going on around me and … actually, I get a lot of work done that way. You know, when I’m in a group, I get kinda stressed out … like, I’m more worried about saying something stupid or what people think about my clothes, or whatever … and seriously, my grades are actually better when I just do the work by myself.

What does this mean for you as an English learner?

Think about how you’re going to be using English in the future.

♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥

If you are more interested in conversing with English speakers and listening to shows, movies, and lectures in English, then focus on spoken English.

- Listen to as much “natural” English as you can. Flood yourself with English! I suggest some good listening resources in this article. My experience from learning French this way is that when you concentrate on understanding as much as you can and focus on “noticing” certain structures, phrases, and words, you eventually absorb them, make them “your own,” and use them in your own speaking.

- Remember that even academic lectures and news broadcasts are still delivered in spoken English. The speakers may use less slang and colloquialisms like I’m gonna or you hafta, but their vocabulary will still be more limited and their structures will be simpler.

- Rely less on textbooks, and more on “authentic” English – the way it’s spoken in real life. Even the best textbooks tend to provide conversations which sound unnatural and “written.” For example, in one textbook I read the following:

A: What about you? What did you do on Saturday?

B: I did not do anything special. I stayed home and worked around the house. Oh, but I saw a really good movie on TV. And then I made dinner with my mother.

In “real life,” the conversation would probably sound more like this:

A. Whadda ’bout y’all? How’d your Saturday go?

B. Ah, nuthin’ to write home about. Mostly just hung out. Got some stuff done around the house, I guess … and oh yeah, I streamed an awesome chick flick. Plus me and mom fixed something for dinner.

- Don’t neglect vocabulary study … you still need it! But focus first on high-frequency words (see the Fry List), idioms, and phrasal verbs.

♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥

If you want to study in an English-speaking country, reading academic texts and submitting essays, reports, or papers, or to work in an international company where you’ll be communicating in writing with English-speaking colleagues, then you’ll need to work on both spoken and written English skills.

- Good English writing is an art. Mastering this art requires years, not months or weeks. As a case in point, the law school where my husband teaches employs two full-time writing instructors for 400 students — almost all of whom are native-English-speaking, American college graduates.

- Just as lots of attentive, focused listening helps develop speaking skills, so lots of reading helps develop writing skills. What should you read? One good rule of thumb is to focus on reading material that you need to write. If you need to write engineering reports, read engineering reports. If you need to write general academic essays, read general academic essays. When in doubt, just keep reading. A great textbook that integrates academic reading and writing is From Inquiry to Academic Writing by Greene & Lidinsky.

- Grammar and syntax, as well as vocabulary, are more important in written English, so you’ll need to focus more on these areas. There are a million and one English grammar books. I prefer Cambridge grammar for British English and the Azar series for American English, but you will find plenty of teachers who prefer others 🙂 My favorite online website for studying grammar is Teacher Paul’s Learn American English Online.

- There are many, many books about becoming a better writer of English. Here are a few different articles listing some “best books about writing.”

10 Books to Help You Polish Your Writing & English Skills

Three Books That Will Immediately Improve Your Writing (Forbes Magazine)

The Best Books for Improving Academic Writing

My personal favorites are The Elements of Style by Strunk & White and The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker.

I also recommend the Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab for lots of practical advice on issues like citations, formatting, subject-specific writing, applications to college and graduate school, etc.