Improving your speaking with a five-item list

Recently I was listening to a psychology lecture by Professor Mark Leary on my favorite video learning site, Great Courses Plus. In discussing how our mind works, he pointed out that talking is almost completely nonconscious (psychologists prefer this term to unconscious): that is, we don’t consciously choose our words when we speak. Words usually come out of our mouths without our really thinking about what we’re saying. We make a conscious effort to choose the right words only in special situations … like when we’re being interviewed or when we have to discuss a sensitive issue with a friend or colleague.

I believe that nonconscious talking is really the same as language fluency. As a fluent speaker of our native language, we can easily talk nonconsciously. But when we’re trying to speak another language, we become all too conscious of what we’re saying.

When we first learn a language, we’re hyper-conscious (that’s my made-up word to mean very, very conscious). We struggle with pronunciation, grammatical forms, vocabulary, putting sentences together. As our fluency improves, our speaking becomes more nonconscious; we are able to speak more quickly, about lots of different topics.

On the other hand, in certain stressful situations, we may return to being more hyper-conscious … we speak with more pauses and hesitations and may repeat what we have just said to make sure we got it right (this is probably why test-takers often do worse on the TOEFL Speaking section).

Unfortunately, as we progress in our language learning, we often pick up bad habits. We get in the habit of making a particular error and repeat it without being aware of the mistake. These errors become, in fact, nonconscious. We don’t notice them and, thus, we don’t correct them. To make matters worse, when we repeat a particular behavior, it becomes embedded (set, planted, rooted) in our brain. And once our brains are wired to make this mistake, it’s difficult to change. Just like any bad habit, it’s very hard to break.

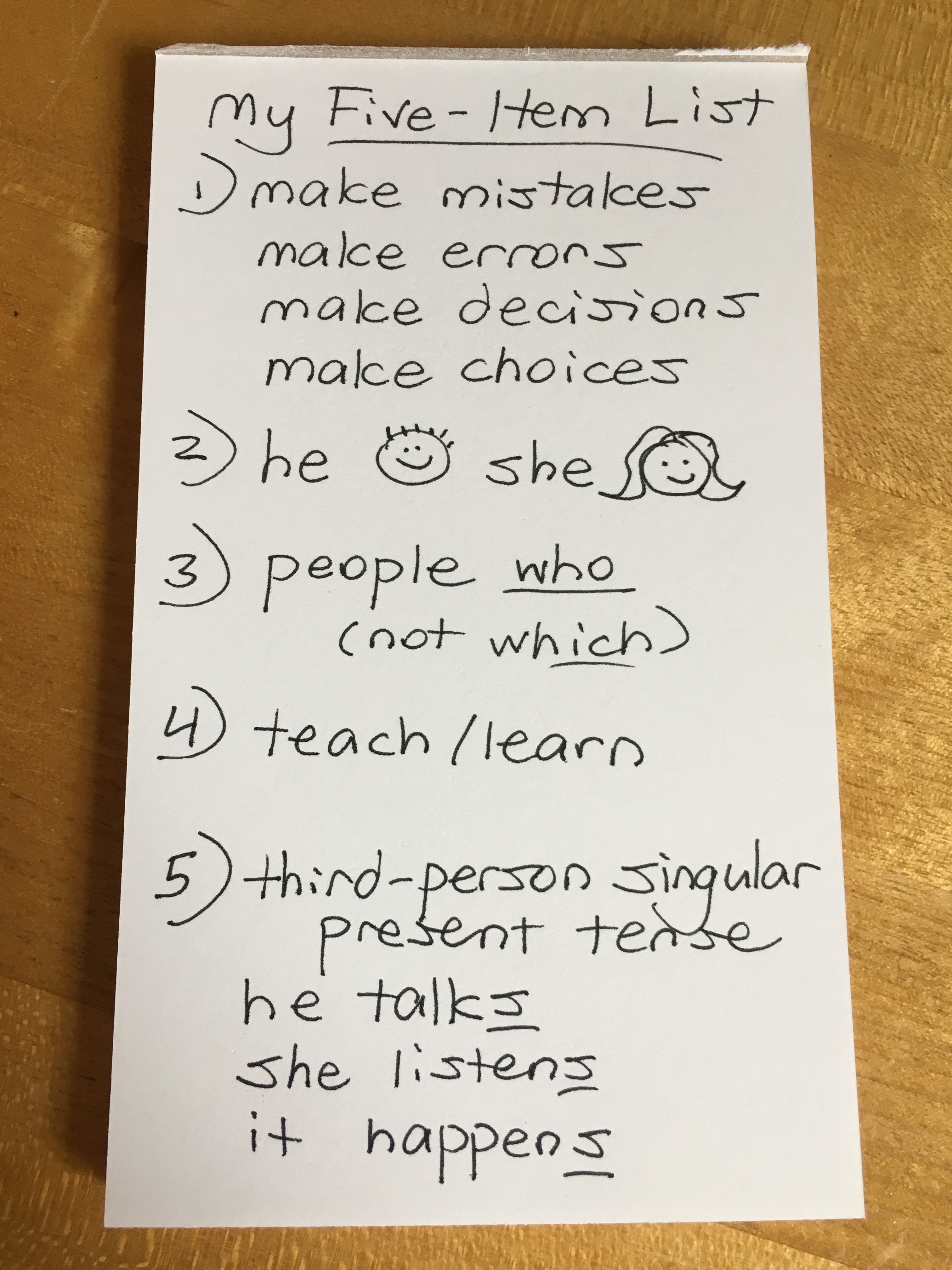

In addition, there are certain expressions, or structures, or phrases that we find difficult to use fluently and nonconsiously. For example, we have problems with using he and she, or with adding the final -s in the third-person singular present tense. We may be able to proceed along in a conversation quite fluently, and then have to pause while we think about how to say something correctly.

So how do we get out of this rut and re-wire (re-train) our brain to avoid making the same mistakes and to become more nonconscious in our speaking?

I suggest using a five-item list. Here’s how it works.

- Start your list with one expression/structure/phrase that causes you problems — either because you have picked up a bad habit or because you tend to hesitate and think consciously about how to say it correctly. I recently had a student who repeatedly said “do mistakes” rather than “make mistakes.” When I pointed this out, she said she knew that she should say “make mistakes” but she’d gotten in the habit of using “do mistakes” instead. Since we’d identified this as a phrase that she used fairly frequently, I suggested that she start her list with this expression, along with a few others that are similar: make errors, make decisions, make choices.

- Once you have an item on your list, practice this expression/structure/phrase regularly, in a variety of ways. For example, my student with the bad habit could repeat a number of made-up sentences like these:

I make mistakes in English.

I made a mistake yesterday.

Making mistakes is common.

I want to avoid making mistakes.

Or, my student who has problems with conditionals could “fill-in-the-blanks” like this:

If I had ——, I would ——- (a certainty)

If I had ——, I could ——– (a possibility)

He could then extend this practice by replacing had with other past tense verbs (like went or saw)

- Your goal for each item is to replace your bad habit with a good habit or to use this particular expression/structure/phrase without hesitation. You will know you have succeeded when you are speaking nonconsciously and you say something like, “I always make a mistake” instead of “I always do a mistake.”

- As you encounter other common items that have become bad habits or cause you to hesitate, add them to your list. Don’t go over five items at one time. When you feel you’ve really mastered something (so that, for example, you say “make mistakes” without giving it any thought), then cross that item off your list.

- Remember that this is a method to re-wire your brain and correct bad habits that have become unconscious. At the same time, to improve your fluency, you’ll also be acquiring new information, like new vocabulary words or new irregular past tense verb forms. By combining both strategies, you will make quicker progress toward becoming a fluent English speaker.

Improving your writing on your own

When you’re on your own, you can quite effectively improve your receptive language skills like reading and listening as well as your grammar and vocabulary. But what about productive skills like writing and speaking? These skills require you to produce something … text or speech … yet how do you evaluate and improve these abilities all by yourself?

This article has some suggestions for improving speaking fluency. Now I’d like to discuss improving your writing.

Most of my students are preparing for TOEFL iBT Writing so let’s talk about that. (Many of these tips, however, can be applied to any sort of writing.)

What can you do, on your own, to improve your writing and get a higher score? In my opinion, just writing essay after essay is definitely not the only and probably not the most effective way to achieve this goal.

Improve your typing

This would seem obvious, but being a slow typist is really going to hurt you when time is of the essence.

I was lucky, because my mother forced my brother and me to take a typing class one summer many years ago. Like riding a bike or swimming, once you learn to type quickly and accurately, it’s a skill you never lose.

First, test your current typing speed. I Googled “typing speed test” and found lots of hits. At this website, I took a three-minute test and tested at 64 WPM (words per minute) with 98% accuracy. Both speed AND accuracy are going to be important on TOEFL Writing. You want to get your ideas down as quickly as possible. And because your rater won’t be able to distinguish between typos and spelling/grammar mistakes, you also want to type accurately. Furthermore, you won’t have that handy spell check and autocorrect to help you!

What is a good typing speed to aim for? According to Mr. Google, 40 WPM is average; anything above that is better. The website mentioned above along with many others offer lessons that can help you to improve your speed. And the satisfying thing about working on your typing skills is that improvement is easily measured and usually happens fairly quickly.

Brainstorm ideas

Many of my students struggle coming up quickly with three main points for the TOEFL independent essay. Yet I find that I can usually generate multiple ideas within a minute or two. Therefore, I think it’s safe to say that this is a skill that can be improved with practice.

Instead of writing a whole independent essay, just brainstorm the topic and see how many different ideas you can generate quickly. Try using both the 100% and 50/50 strategies. Find various topics in TPOs (TOEFL Practice Online) or TOEFL study guides.

Let’s take this topic (TPO 50) as an example:

Do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

All university students should be required to take history courses no matter what their field of study is.

Use specific reasons and examples to support your answer.

So I could first try generating at least three points that are 100% for or 100% against. Try to think of a minimum of three, but keep going if you can … when you’re actually writing the essay, being able to choose the best three, and not the only three will be a great help. The three you choose should be the points that you can support the most effectively and quickly.

In favor of requiring history courses:

- Knowledge of your country’s history makes you a better citizen.

- Greater knowledge of history can make you appear more intelligent.

- Knowledge of world history helps you if you need to interact with other nationalities.

- Studying history requires good reading and analytical skills that help in lots of different fields.

- Studying history helps you understand and appreciate literature and art better.

- The best universities offer a liberal arts education which requires studying history as well as other fields like literature and social sciences.

Against requiring history courses:

- Most high schools teach enough history to cover the necessities.

- Required history classes would create too much work for university students who are already busy enough.

- History is not relevant to some fields like engineering and computer science.

- Students can learn history on their own by reading books.

- History professors may be biased and even provide students with misinformation.

- History is not relevant to our society today; it’s the future that matters.

Next you could generate ideas for a 50/50 strategy, meaning that whether students should be required to take history depends on factors such as:

- The type of university (liberal arts colleges usually require history; specialized schools like engineering colleges may not)

- The depth/quality of history instruction in high school (if instruction is good in high school, then not necessary in university)

- The availability of qualified history professors (does the university have enough professors to teach all students?)

- The quality of instruction in history at the university (are the history professors good, unbiased, well-trained?)

- The relevance of history to their field of study (not relevant for computer science, might be relevant for business majors who want to work abroad)

- Type of history taught (world history not important; history of country is)

Each point that you generate would be used as the main idea of a paragraph and would be presented in the topic sentence of that paragraph. But in addition, you should also practice brainstorming ideas to support each of these points. These ideas would be the supporting details included in the rest of that paragraph. For example, let’s take the very first point:

- Knowledge of your country’s history makes you a better citizen.

You could quickly write:

- learn more about how a democracy functions

- get a better understanding of our political parties

- make more informed decisions at the voting booth

- gain more pride in our country; also understand its missteps and mistakes

Finally, as you generate ideas, remember that always, always, always it’s better to be specific and focused. For this particular essay topic, don’t write about university students in general. Center all your points and supporting ideas around university students in your particular country. If your country isn’t a democracy, for example, the supporting ideas above would make no sense.

Write. Rest. Correct Errors.

In addition to working on your typing and generating ideas, there will also be times when you practice writing on your own by … surprise! … actually writing something! When you do this, I recommend a three-step process of writing, resting, and error correction.

- When you’re practicing for the TOEFL iBT, I think it’s best to follow the requirements of the specific writing task. For example, for the independent essay, you should give yourself exactly 30 minutes from start to finish. If possible, you should do a quick proofreading toward the end of your 30-minute writing time. More intensive error correction comes later.

- Next I recommend that you set your writing aside for a while. I find that when I’m too “close” to my writing, I can’t read it objectively. And yet that’s what you need to do to correct it effectively. I recommend doing the error correction the following day.

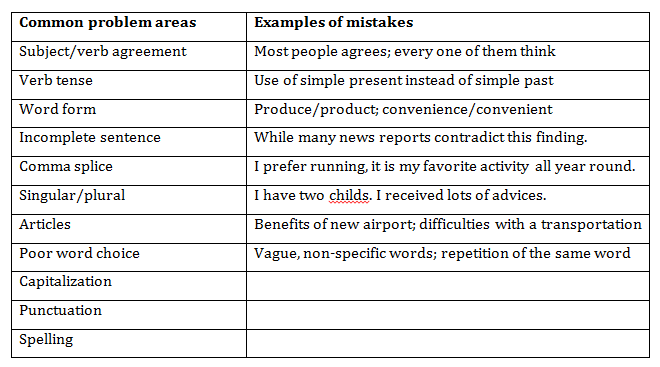

- Error correction basically involves trying to spot (and figure out how to fix) as many errors as possible in your written work. This is more than a quick proofread because you’re really going to focus on your written work and identify every single error you’ve made. Obviously, if you don’t know it’s an error, you won’t be able to spot it.

To catch more errors, read your work out loud. Scan each sentence carefully. Does it have a subject and verb? Do subjects agree with verbs? If there is a dependent clause (beginning with a subordinating conjunction like because, when, if), is there also an independent clause? Did you use the correct tense? Are you connecting sentences with commas (which is incorrect) rather than punctuating with semicolons or periods? Did you use the correct form of each word? Is there a better, more specific word you could have used instead?

Finally, once you’ve identified as many errors as you can, use a subsequent study time to focus on one specific area, whatever seems to be a particular weakness for you. Two websites that I recommend for grammar are:

For general help with writing, try:

The TOEFL integrated essay

During the TOEFL iBT, you will have two writing tasks. The second and longer task is the independent essay. The first is the integrated essay.

In my opinion, your writing skills are less important in the integrated essay; of more importance is your listening ability and, to a lesser extent, your reading ability. In the essay, you must make clear connections between the points in the reading and the points in the lecture. Obviously, if you don’t understand what you hear in the lecture, this will be very difficult, which is why the integrated writing task is truly integrated. Without being able to integrate listening comprehension, reading, and writing skills, you will not obtain a high score.

Neither the reading nor the lecture in the integrated writing task is as difficult as the texts in the Reading section or the lectures in the Listening section. You will have ample time (three minutes) to identify the main points in the reading passage. Also, after the lecture, you will be able to view the reading passage until the end of the writing time. The lecture is short (about 2 to 2 ½ minutes) and clearly structured; in addition, since the content of the lecture relates directly to the reading you’ve just completed, it’s easier to understand.

Nevertheless, until your reading and listening skills are developed well enough for you to understand the three points of connection between the reading and the lecture, there’s little reason to put much effort into practicing the essay itself. It’s better to work on your writing skills by attempting the independent essay and continue practicing reading and listening skills separately. In fact, initially I recommend that rather than trying to write an integrated essay, you simply make tables of the main points (as I’ve described below) to see if you’ve identified them correctly.

A sample writing task

Let’s take a sample integrated writing task to discuss how to approach it.

The reading passage from TPO (TOEFL Practice Online) 33 is as follows. You would have three minutes to read this.

Carved stone balls are a curious type of artifact found at a number of locations in Scotland. They date from the late Neolithic period, around 4,000 years ago. They are round in shape; they were carved from several types of stone; most are about 70 mm in diameter; and many are ornamented to some degree. Archaeologists do not agree about their purpose and meaning, but there are several theories.

One theory is that the carved stone balls were weapons used in hunting or fighting. Some of the stone balls have been found with holes in them, and many have grooves on the surface. It is possible that a cord was strung through the holes or laid in the grooves around the ball. Holding the stone balls at the end of the cord would have allowed a person to swing it around or throw it.

A second theory is that the carved stone balls were used as part of a primitive system of weights and measures. The fact that they are so nearly uniform in size — at 70 mm in diameter — suggests that the balls were interchangeable and represented some standard unit of measure. They could have been used as standard weights to measure quantities of grain or other food, or anything that needed to be measured by weight on a balance or scale for the purpose of trade.

A third theory is that the carved stone balls served a social purpose as opposed to a practical or utilitarian one. This view is supported by the fact that many stone balls have elaborate designs. The elaborate carving suggests that the stones may have marked the important social status of their owners.

After the reading, you will hear a lecture from a female professor:

None of the three theories presented in the reading passage are very convincing.

First, the stone balls as hunting weapons. Common Neolithic weapons such as arrowheads and hand axes generally show signs of wear, so we should expect that if the stone balls had been used as weapons for hunting or fighting, they too would show signs of that use. Marry of the stone balls would be cracked or have pieces broken off. However, the surfaces of the balls are generally well preserved, showing little or no wear or damage.

Second, the carved stone balls may be remarkably uniform in size, but their masses vary too considerably to have been used as uniform weights. This is because the stone balls were made of different types of stone including sandstone, green stone and quartzite. Each type of stone has a different density. Some types of stone are heavier than others, just as a handful of feathers weighs less than a handful of rocks. Two balls of the same size are different weights depending on the type of stone they are made of. Therefore, the balls could not have been used as a primitive weighing system.

Third, it’s unlikely that the main purpose of the balls was as some kind of social marker. A couple of facts are inconsistent with this theory. For one thing, while some of the balls are carved with intricate patterns, many others have markings that are extremely simple, too simple to make the balls look like status symbols. Furthermore, we know that in Neolithic Britain, when someone died, particularly a high-ranking person, they were usually buried with their possessions. However, none of the carved stone balls have been actually found in tombs or graves. That makes it unlikely that the balls were personal possessions that marked a person’s status within the community.

Notes on the reading and lecture

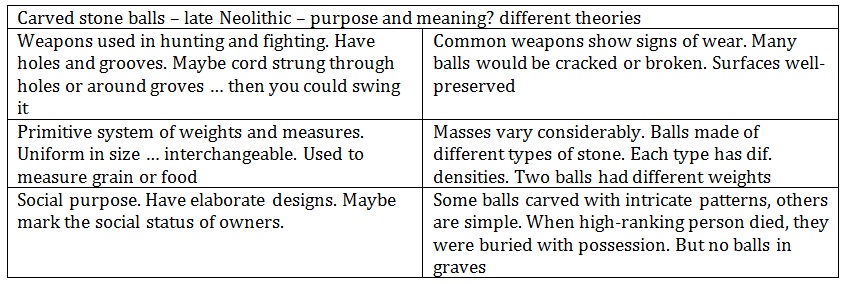

I suggest that you take notes using a table like the following:

In the top box, based on information in the introductory paragraph, you’ll make brief notes on the subject of the reading passage … just enough so that you remember what it’s about. You’ll be able to go back to the text after the lecture, so you don’t need to be very detailed here.

On the left-hand side of the table, you’ll write the three main points of the reading. You will find one key point and a few supporting details in each paragraph following the introduction. Remember, you’ll be going back to the text after the lecture. You’ll have another chance to read for details. During this three-minute reading time, what’s most important is that you clearly identify and understand the three main points. If you do this, you’ll be able to understand the lecture much better.

During the lecture, you’ll listen for the lecturer to respond to the three main points. Listen for phrases like first … second … third and first of all … secondly … finally; they will signal when the lecturer transitions from one point to another. You will only have one chance to listen to the lecture, so good notes (or a good memory) are essential here. If you miss any of the three key points in the lecture, you won’t be able to score higher than a 3 out of 5. Usually, the lecture includes at least two supporting details to support each point, and ideally you will include all of them in your notes and then in the essay itself.

The writing task

After you finish the lecture, you’ll have 20 minutes to write your essay of around 150 to 225 words. Although TOEFL study guides say that some lectures support or strengthen the information in the reading passage, this is highly unlikely. The TPOs, which are “retired” actual TOEFL tests, contain only tasks in which the lecturer challenges or disagrees with the reading passage.

Although the rater will definitely evaluate the quality of your writing, your ability to successfully describe the relationship between the ideas in the reading and the lecture for each of the three main points is key to getting a top score. Even William Shakespeare himself would not get a 5 unless he understood what he heard in the lecture. 🙂

In your essay, your emphasis should always be on the material that is in the lecture. The rater knows that the material in the reading is available to you while you’re writing; therefore, merely rephrasing what the text says will gain you little advantage.

Because the writing task is so standardized, test-takers tend to follow certain templates or formulaic language that they’ve encountered at test-preparation websites or courses. This is acceptable to a certain degree, but remember that if you’ve been taught to write in a certain way, thousands of other students have probably been taught the same way. Your rater will recognize these formulas instantly, and will be more impressed if you can avoid such a monotonous approach and write your essay with slightly more creativity and originality.

The first paragraph

Your first paragraph must contain three essential points, which you should be able to state in no more than two or possibly even just one sentence. The key information includes:

1) enough information about the topic so that a reader unfamiliar with it will understand it — you will identify the REAL thesis and restate it without using the exact same wording as the reading

2) what the author of the reading is doing (for example: offering some theories, suggesting some reasons, discussing some beliefs)

3) what the lecturer is doing (almost always refuting, disagreeing, or contradicting, but if you can be more specific, you should be)

Here are some examples of introductory paragraphs:

The salinity of California’s Salton Sea has been rising steadily in recent years. While the author suggests several solutions to reverse this trend, the lecturer believes these are unrealistic and impractical. (TPO 54)

The reading passage cites a number of social benefits resulting from high taxes placed on cigarettes and unhealthy foods. However, the lecturer challenges the arguments in favor of such taxes. (TPO 53)

Although the text suggests that colonizing asteroids might be a better option than sending people to the moon or to Mars, the lecturer disagrees. (TPO 52)

The reading discusses several beliefs that humans have developed about elephants. However, the lecturer believes that these ideas are misguided and reflect our misunderstandings about elephant behavior. (TPO 51)

When writing your essay, you’ll want to use a variety of reporting verbs to describe what the reading and the lecturer say. Avoid using the same verbs over and over again; also, try to make them precise and specific. Is the author claiming or merely suggesting? Is the lecturer pointing out or contradicting? My article on reporting verbs should provide you with lots of information to make these distinctions clearly.

However, rather than using variety, I think you should be consistent in how you refer to the reading and the lecture. If you choose to call it the reading, stay with that. Or call it the text or the author. In the same way, call the person giving the lecture either the speaker, the lecturer, or the professor and stick with that. You can also use the pronouns he or she; just make sure you get the gender correct.

Suggestions for the subsequent paragraphs

Some of my students tend to follow a very repetitious and monotonous structure: variations of The reading says this, but the lecture says this … The reading says this, but the lecture says this … The reading says this … and so on and so forth. I recommend that you vary this structure a little bit if you can. Here are three ways that you can do this. Some alternative word choices are included, but consult my article on reporting verbs for a more extensive list.

Although (while) the author states (believes, notes, suggests) that [a point from the text that you restate in your own words], the lecturer disagrees. She (he) points out that … [try to include two ideas from the lecture]

The lecturer refutes (disputes, rejects) the idea (theory, belief, suggestion) that [another point in the text]. She (he) claims (suggests, points out) that …. [try to include two points from the lecture].

The author asserts (contends, argues) that [another point from the text]. However (in contrast), the lecturer (disputes, contradicts, disagrees with) this (statement, idea, opinion). He (she) maintains (affirms, observes) that [two ideas from the lecture].

A sample essay

Finally, what does an integrated essay look like? Here’s my attempt at answering TPO 33.

Archaeologists have found round, carved stone balls dating from the late Neolithic period at several sites in Scotland. Although several theories about the meaning and purpose of these balls are discussed in the reading, the lecturer strongly disagrees with their validity.

First, although the reading states that the presence of holes and grooves in the balls indicates that they might have been used as some type of weapon, the lecturer refutes this idea. She points out that common weapons such as arrowheads found at these sites show signs of wear. If used as weapons, these balls would likely be cracked or broken. Their well-preserved surfaces contradict the theory that they were used as a weapon.

Second, the lecturer refutes the theory that the stones, which are uniform in size, could have been used in a primitive system of weights to measure grain or food. She notes that although interchangeable in size, the masses of the stones vary considerably. Because the balls are made from different types of stones, the balls have different densities, and thus different weights. So it would not have been possible to use them as a device for common measurement.

Third, the reading proposes that, due to their elaborately carved designs, the stones might have had a social purpose and been used to mark the social status of their owners. The lecturer disagrees. She observes that although some stones have intricate patterns, others are quite plain. Furthermore, she points out that, in the Neolithic period, those people of higher status were buried with all their possessions. Yet no graves have been found with balls in them, making it unlikely that the balls were a marker of social status.

Reporting verbs

The English language offers a multitude of words that a writer can use to describe what something or someone says. These words are commonly called “reporting verbs.”

However, these verbs can have subtle shades of meaning and if you don’t use the right one, you risk misusing them … undercutting or distorting their meaning and maybe even confusing your reader.

It is also important to recognize how a particular verb is used in the context of the whole sentence. Usually, we follow the reporting verb with a direct object (for example, state the idea) or with a dependent clause (for example, state that dogs are intelligent animals). Sometimes, a particular verb requires a preposition (for example, object to). Study the examples I give below so you make sure you get this right.

For a task like the TOEFL integrated essay or a short academic paper, you don’t need to master a huge number of reporting verbs. Being able to confidently and correctly use a smaller group will be all you need to communicate effectively. In addition, you’ll also want to acquire a helpful number of nouns that are derived from these verbs.

In spoken English, we frequently use forms of say, talk about, or think. For example, my son says cats are more intelligent than dogs. This book is talking about animal intelligence. My daughter thinks dogs are more intelligent than cats. In writing, however, you will want more variety and more precision.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

State has a very neutral and non-forceful meaning. We state facts. The author states that cats are more intelligent than dogs. A statement is something someone says. The university might issue a statement about a new policy. You might make a statement to the police if you witness a crime.

I’m fond of the word posit, which has the same meaning as the phrasal verbs put forward or set forth. This word implies that the person is stating something that they believe is true. The author posits that we should regard cats and dogs as intelligent beings.

Discuss is also a neutral word, but is usually used when someone is talking about a number of things, perhaps for a longer period of time. An author might discuss different kinds of intelligence. You might discuss your homework assignment with a friend. Your teacher might encourage a class discussion.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Assert is a stronger word than state. The author asserts that neither cats nor dogs are very intelligent. Someone accused of a crime might assert their innocence. You make an assertion about something you strongly believe.

Other verbs that are very close in meaning to assert are maintain and affirm. The article maintains that humans are more intelligent than animals. The professor affirms the idea that there is more than one kind of intelligence.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Argue is even more forceful than assert. The author argues that his cat is more intelligent than many humans. In an argument, people are having a disagreement. So to argue implies that there is a counter-argument even though it is not necessarily stated explicitly.

Another verb that is very close in meaning to argue is contend. It also implies a more argumentative stance. The author contends that it is impossible to measure intelligence accurately. If you disagree frequently with a friend, you might try to avoid points of contention … those issues that you argue about. If you are always fighting about the same thing, we idiomatically call that issue a bone of contention (probably from the image of two dogs fighting over the same bone).

Debate can be used if we are explicitly referring to two or more parties; thus, although it is quite formal, it can be used in the TOEFL integrated writing task where an author and speaker take contrasting positions. The author and speaker debate whether life exists on Mars. The authenticity of the artifact is debated by the author and the speaker. The author and speaker debate the significance of the evidence provided by the animal researchers.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Other useful reporting verbs with different shades of meaning include:

Claim. When you claim something, it may or may not be true. The author claims there is life on Mars. He makes a claim about the existence of life on Mars. You generally don’t make a claim about something that’s absolutely certain; you believe it’s true, but others might not. In other words, you don’t claim that there are 24 hours in a day.

Believe. This verb also implies that you may not have facts to prove your belief. If the author believes that dogs are more intelligent than cats, this suggests that others may not believe this.

Suggest. Suggesting something is not very forceful. It implies there are alternate possibilities. The evidence suggests that there may be water on Mars. You normally follow suggest with a modal verb form. He suggests there might be several solutions to the problem. She suggests that they could approach the issue from a different point of view. You make or offer a suggestion.

Propose. This is very similar to suggest but it’s a bit more formal. The author proposes that further research might be necessary to determine the validity of the analysis.

Recommend. This is similar to suggest and propose, but I think it’s stronger and implies that a judgment has been made and a preference indicated. You could suggest or propose several different solutions, for example, but you are likely to recommend one particular solution.

Imply. This is even less forceful than suggest. You imply something without actually saying it directly. You make an implication. Figuring out what an author implies is a popular type of question on many reading tests. We sometimes say that you have to “read between the lines” to determine what the author is implying.

Note, point out, or observe. These are useful, fairly neutral verbs that could be used to describe an observation the author has made or a fact that they have noted. These verbs wouldn’t be used to describe stating a position or making a claim. The author notes that cats generally live longer than dogs. He points out that many cats live over 15 years. He also observes that human beings become very attached to their pets. He makes an observation.

Illustrate. You illustrate something with an example or illustration. The author illustrates his idea that dogs are more intelligent than cats by telling a story about his German Shepherd and his cat. You can also provide or offer an example or illustration.

Hypothesize/theorize. These verbs are especially helpful in the TOEFL iBT integrated writing task, in which the reading often presents theories that the lecturer disputes. What’s the difference between them? For scientists, a theory is well-tested and backed by evidence (such as the theory of evolution), while a hypothesis is merely a possible suggested explanation or outcome. The integrated writing task generally doesn’t make this distinction, and theory and theorize are more frequently used even though hypothesis and hypothesize would probably be more appropriate. This may be because theory and theorize are more common and recognizable for test-takers; in addition, hypothesize is harder to spell and the plural of hypothesis is tricky … it’s hypotheses, not hypothesises. However, this is just my hypothesis 🙂

Speculate. If you want a variation on hypothesize/theorize that is less scientific, speculate is a great word that basically means the same thing. Although the reading speculates that cats may be trained to solve simply problems, the lecturer disagrees.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Now that we’ve covered synonyms for saying things, how do we deal with someone’s counterarguments? What if someone disagrees with the author?

I guess human beings are argumentative by nature, because there are lots and lots of words to express these ideas! What you need to be careful about, when you’re writing, is making sure you include a direct object (if needed) and the proper preposition (if required).

Disagree is one of the few verbs that doesn’t need a direct object. You can simply disagree. The author states that dogs are more intelligent than cats, but the professor disagrees. He disagrees with that statement.

Object (notice that when pronouncing this verb, you put the stress on the second syllable, ob-JECT) can also be used without a direct object (pronounced OB-ject). While the author states that dogs are less intelligent than cats, the professor objects. He objects to this idea. However, the author disagrees with this objection.

Verbs of disagreement that must have a direct object include contradict, dispute, oppose, rebut, reject, and refute. They should not be followed immediately by a dependent clause (for example, that cats are more intelligent). If you want to use a dependent clause, you must have it modifying a noun (such as fact, statement, assertion, belief, or idea) that serves as the direct object.

The professor contradicts the claim that cats are more intelligent.

The professor contradicts.

The professor contradicts that cats are more intelligent.

The lecturer disputes the author’s statement.

The writer opposes his assertion.

The author rebuts the idea that cats and dogs have equal intelligence.

The scientist rejects the belief that intelligence in animals can be measured accurately.

The text refutes the finding that cats are more affectionate than dogs.

Cast doubt on is a very popular phrase my students use for TOEFL integrated writing, but I am not a big fan. Not only do I rarely see this used in print but it is also weaker than the preceding verbs. Doubt is similar to question. When you doubt or question something, to me it implies that you might change your mind, whereas the lecturers in the TOEFL integrated writing section are usually more forceful in their opinions! They are more likely to disagree with, refute, rebut, contradict, or oppose an idea in the reading passage, rather than simply doubt it. 🙂

Criticize is another possible verb of disagreement. I think criticize connotes a more personal and direct confrontation. You might criticize a decision or a policy.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Finally, what if an author actually agrees with something?

As with disagree, agree doesn’t require a direct object. You can agree. Or you can agree with something or someone. You can also concur, or concur with an author.

Corroborate means not only to agree, but usually to provide additional support. The professor corroborates the point in the text by noting that many experiments have proved that cats are very intelligent.

Concede, on the other hand, implies that you have given in after having previously held a different viewpoint. It suggests a certain reluctance in accepting a statement or position. The author concedes that cats are intelligent, but points out that more research should be performed to ascertain their exact degree of intelligence.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Believe it or not, there are many more reporting verbs in the English language. But I believe these are enough words for most students and test-takers to accurately describe what a particular author or lecturer is saying, as well as to compare and contrast different points of view.

And if you’re not sure exactly how to use reporting verbs in your writing, this article may help.

4, 3, 2 …. blast off to fluency!

Tests like TOEFL are supposed to assess English proficiency but, in terms of speaking, what exactly does that mean?

One linguist has noted that how well you speak basically includes three factors:

Fluency: How quickly you are able to produce speech. Are you able to respond quickly to questions? Is your speech sustained and automatic? You may pause from time to time (as everybody does) as you consider your ideas, but your response is not hesitant or fragmented. Your speech is fluid and flowing, not choppy and broken.

Accuracy: How many errors you make. How effective are your word choices? Do you make grammar or vocabulary errors that confuse your listener or obscure your meaning? Do you refer to a woman as he or use the simple present to talk about something in the past? The more precisely and accurately you produce language, the better.

Complexity: The complexity of the linguistic structures (things such as subordinate clauses and modal verbs) that you use. Consider the following question. What do you like to do on vacation?

Less complex response: I like to go to the beach. I can swim there. I can meet new people. I can go wind-surfing sometimes. I like the beach in the summer. It’s hot then. The water will feel good.

More complex response: I really enjoy going to the beach when I’m on vacation. I love swimming and, of course, that’s a big part of my vacation but I also enjoy meeting new people when I’m there. Like last year, I actually learned to wind-surf from a guy I met on the beach. Of course, the beach is always going to be best in the summer because the hot weather makes it even more refreshing when you plunge into the cool water.

So how do you become a more fluent speaker?

If you don’t live in an English-speaking country, one obvious way is to take English classes or lessons where you can speak in English with your teacher and/or classmates. You may also find a group or local meeting place where people practice their English.Perhaps you have a friend or family member who speaks English and would be willing to converse with you. Or you may have a job where you need to use English.

For those living in an English-speaking country, you would expect that finding opportunities to practice wouldn’t be an issue. However, I’ve had students living in the U.S. who really spend very little time actually speaking English. If this is your situation, I suggest you actively seek out opportunities to speak English. Look for classes, interest groups, social occasions, volunteer jobs … anywhere where people are going to be conversing with you. When in doubt, use social media and your local library to find resources and ideas.

Sometimes, though, your opportunities to speak English may be more limited. You may have a class or lesson that occurs just once a week. You may be a mother or father staying at home with your children. You may have a job in the U.S. but not much chance to interact with your co-workers … or maybe your co-workers all speak your native language. What do you do then? A modified form of the 4/3/2 technique may be your answer.

The 4/3/2 technique is an effective, time-tested method that classroom teachers use to develop speaking fluency. The original technique works like this:

- Learners work in pairs with one acting as the speaker and one as the listener. The speaker talks for four minutes on a topic while their partner listens.

- The pairs of learners change, and the speaker now gives the same information to a new partner for three minutes.

- The pairs change yet again and this time the speaker gives their information in a two-minute talk.

The 4/3/2 technique is effective for several reasons.

- It is meaning-focused. The speakers are communicating a particular message under “real time” pressures, as they would be doing in an ordinary conversation.

- It doesn’t require the speakers to use unfamiliar vocabulary or grammar. The speakers merely use the words and structures they already know.

- The time pressure encourages the speakers to perform at a higher than normal level. They will speak more quickly, hesitate less, and use larger “chunks” of language as they try to communicate the same content in less time.

Although this technique was designed for a classroom setting where students could be paired up and switch partners regularly, you can still make this method work for you outside a classroom.

- You could use it with one listener … a teacher, a language partner, a family member. Instead of switching listeners, you just talk about your topic three times with the same partner, first for four minutes, then for three minutes, and finally for two minutes.

- You could use it by yourself. Instead of a partner, use your phone to record and time yourself. Listen to the recording after each turn (four-, three-, two- minutes) and make your own assessment. Hopefully each time you will hear less hesitation and longer chunks of speech with fewer errors and stronger word choices.

- If you are preparing for the independent TOEFL speaking questions, which require 45-second responses, try a 3/2/1 variation. Once you get down to a one-minute answer with the same content as a three-minute answer, you’ll be in good shape for the TOEFL.

What sort of topics should you talk about in this exercise? Basically, anything that you feel comfortable talking about, whatever you’re interested in. If you are preparing for TOEFL, study guides have lots of practice questions and you could also use the Chinese websites with TPO (TOEFL Practice Online). I especially like the pages and pages of Independent Writing topics in the Official Guide to the TOEFL Test. Although these are provided as essay topics, they serve equally well as discussion questions.