Becoming a better reader

How can I improve my English reading skills, especially when it comes to the academic reading in the TOEFL iBT?

Because there are so many different strategies I recommend, I’ll give my advice in two separate articles — the first dealing with general strategies and the second with skills needed for reading tests.

Vocabulary

I’ve already written a series of articles about vocabulary starting with this one. And in my opinion, when it comes to reading quickly for general comprehension (not what we call a close reading), knowledge of vocabulary is much more important than knowledge of grammar. From my own experience reading French for many years, I don’t pay much attention to grammatical structures as long as I get a basic sense of subject/verb/object, past/present/future, and basic parts of speech. But if I don’t know a word, it can make all the difference in whether I understand what a text is saying.

Vocabulary knowledge is also essential for doing well on the Reading section of the TOEFL, as I’ll describe in my next article. Thus, a fundamental part of improving reading fluency will focus on continually acquiring new vocabulary. Don’t stop! You will never ever know enough words.

Extensive Reading

One of the first things I ask my students is whether they enjoy reading in their native language.

Some people are “ born readers” and some aren’t. Although I think everyone can increase their love of reading, given the right reading material, I don’t think you can essentially change your attitude. If you do love to read, you’re in luck. As an English and American Literature major, I can tell you that some of the greatest works in world literature have been written in English. Being able to read them in their original language rather than a translation may be all the motivation you need to work hard on your reading skills.

But whether you love reading or not, reading should be essentially enjoyable. Nothing kills the pleasure like struggling to understand every other word. This is why teaching professionals advocate extensive reading.

Extensive reading happens when a reader pays attention to the meaning of the words, and not the words themselves. And studies have shown that for this to occur, readers need to be familiar with 95 to 99% of the words they encounter.

Think about that. You should know (in the sense that you have a good understanding of the meaning of a word; if “inner translation” is going on in your head, it’s rapid and almost unnoticeable) at least 95 out of every 100 words you read. Ideally, you would know 99 of them.

But here’s the problem. If you aren’t a very good reader, how do you find material that’s easy enough to read? In my classroom, my reading students used graded readers, which are written for adult learners of English and come in a range of reading levels based on vocabulary and sentence structure. You may be fortunate enough to have access to these kinds of readers through a public or university library or you may try to locate them online. Well-known publishers of graded readers include Cambridge, Oxford, Macmillan, Pearson, and Scholastic. This is a chart that gives some common series and their levels. If you want to assess your current reading level, try this placement test. Another option, if you don’t have access to graded readers for adults, is to read chapter books written for English-speaking children. Although they may seem a bit babyish, these books are ideal for beginning and intermediate readers. I particularly like Cynthia Rylant’s series: Henry and Mudge (a boy and his dog) and Mr. Putter & Tabby (an elderly man and his cat).

A few recommendations made by the researchers Nation and Wang include:

- Read at least one graded reader each week.

- Read at least five readers at one level before advancing to the next level.

- Read at least 15 – 20 graded readers each year, and preferably 30.

- Read more books at the later levels than the earlier levels.

A resource you can use to evaluate online reading material is to copy and paste a sample of the text into a readability checker. Texts are assigned a grade level corresponding to grades in US schools (with 12th being the highest). For comparison, my blog article Give or Get? is scored Grade 6 (fairly easy to read) while the TOEFL reading passage that I’m going to use in my next article is Grade 12 (fairly difficult to read).

Speed Reading

Reading quickly is not going to help you much with the TOEFL iBT Reading section (although it will help somewhat with the Speaking and Writing integrated tasks); we’ll talk about that in the next article. But if you need English for academic study or a career, you will want to avoid plodding along when you read. Being able to pick up your pace will make your life a lot easier!

To test your current reading speed, just Google “testing reading speed” and you’ll find lots of different sites. I tried this one at the Wall Street Journal and found my reading speed ranged from 432 – 492 words per minute, with 100% comprehension.

Obviously, your reading speed is going to be affected by the difficulty of the text (including vocabulary, structures, and content). A reasonable reading goal for easy reading material (known words, basic grammatical structures, simple content) is around 250 words per minute. And you need to read carefully enough that you’re able to understand and remember what you read … this is why tests of reading speed include comprehension questions at the end.

One of the best ways to improve reading speed is to use graded readers that are a much easier level for you. Here you focus not on meaning (which improves vocabulary and understanding) but on speed alone. Use a stopwatch to test your speed and don’t be afraid to repeat reading the same material over and over. Keep a log of your progress and make a game of the whole process.

Finally, a bit of advice from my own experience reading French. Even now, after 40 years of reading French, I find that with challenging texts (those written for French-speaking adults, including authors like Proust who challenge even French readers), I often activate my “inner translator.” In other words, every word I read in French gets mentally translated into English before it’s processed. I have to make a really conscious effort to avoid that to pick up my reading speed.

So, we’ve talked about reading a lot and reading quickly. In the next article, we’ll talk about reading closely and carefully, especially in the context of a specific TOEFL Reading passage.

The TOEFL Listening section

How can I get a better score on the TOEFL iBT Listening section?

After hearing that question from a number of students, I decided to take a few practice tests myself. No better way to figure out how to tackle a challenge than to actually do it yourself! And here are some thoughts I have about the test.

What Type of Learner Are You?

Most people are aware that there are different types of learners, classified by how they prefer to receive and process information. Auditory learners like to listen; visual learners like to see; kinesthetic learners like to touch. You may have already figured out what type you are.

I’m a visual learner. If someone gives me directions orally, I usually get them mixed up. I much prefer a set of written directions, or a map. Thus, I find listening tasks more difficult to follow. Lectures are easier for me if I’m given a handout or provided with an accompanying PowerPoint.

You can’t change the type of learner you are. Just be aware that if you aren’t an auditory learner, any listening task, whether in English or your native language, is going to present a bigger challenge. And this may affect your approach.

Notes or No Notes?

I have had a few students who don’t take notes, ever. Not in university, and not on the TOEFL. But, as a visual learner, this is not my approach. Taking notes really helps me not only to put what I hear into a visual format, but also to focus better on the content. I’m not sure I could remember what I heard if I didn’t have something written down.

So unless you’re an auditory learner with an excellent memory, I recommend that you take notes. However, note-taking may well distract you from actually listening, and therefore must be done strategically.

How to Take Notes?

Personally, I don’t believe there’s one right way to take notes. I’ve had students who’ve mentioned a particular note-taking method that an online site, study guide, teacher, or friend who got a high score has recommended. But I say … find the method that works for you. It’s like when you’re trying to lose weight. Go online and you’ll find thousands of diets that have plenty of followers all saying that this is the perfect way to lose weight. What they’ve found, actually, is the right way for them, but maybe not for you.

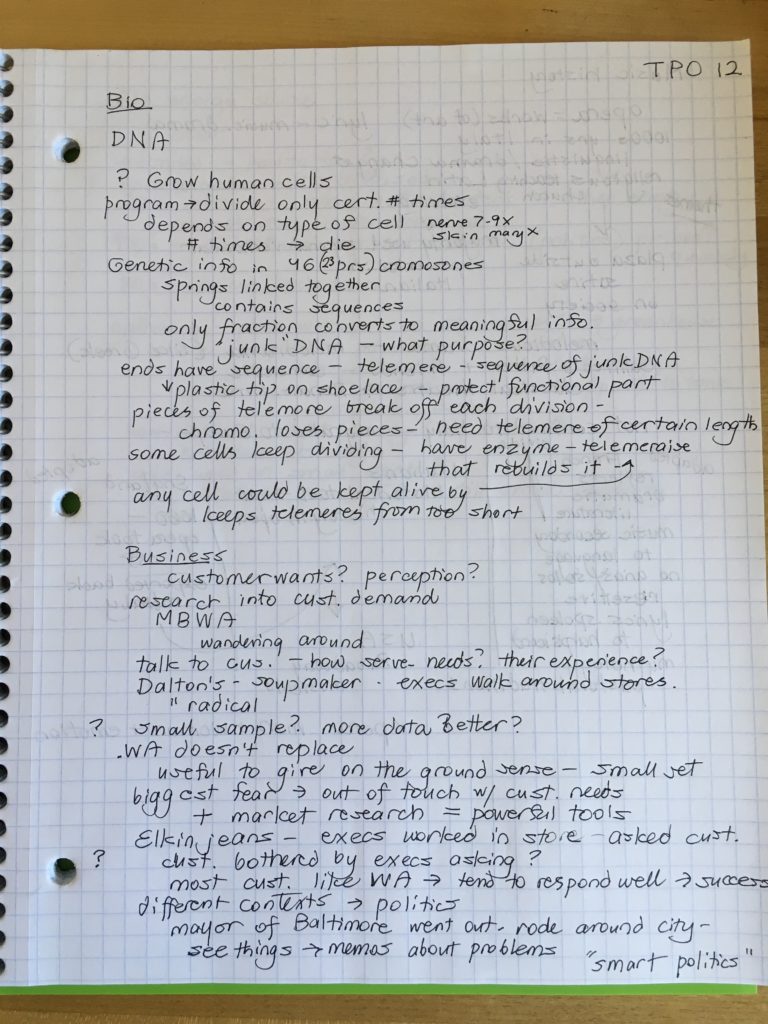

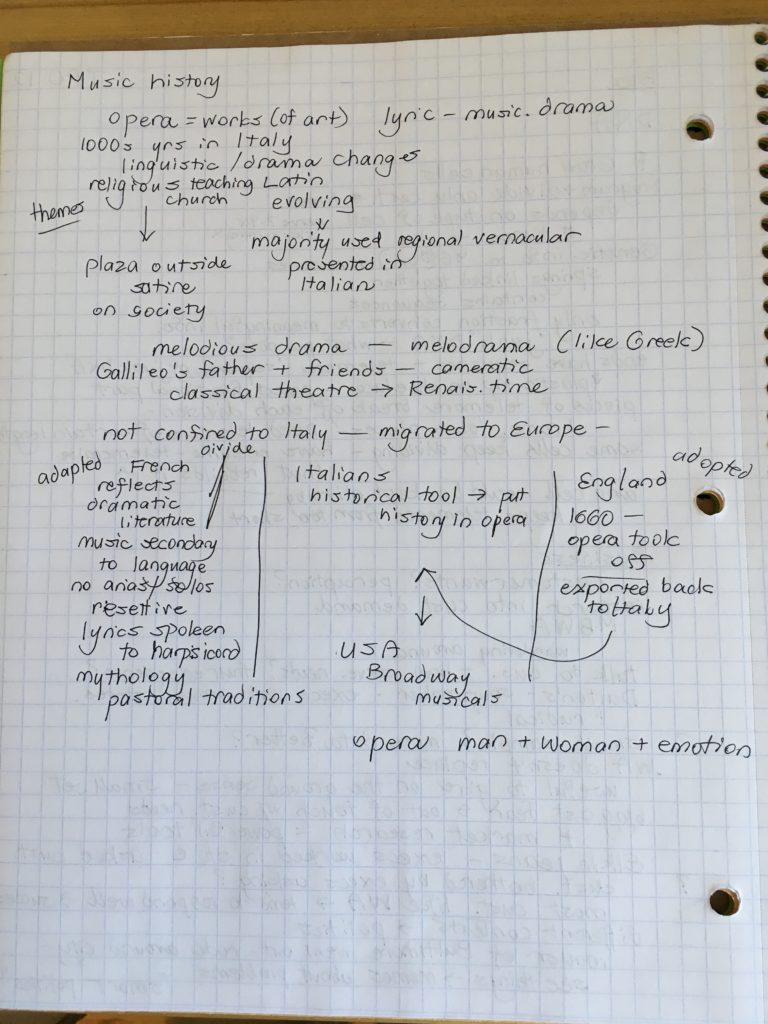

So, through practice, identify what type of note-taking works best for you. Ideas to consider:

- Write at least some of your notes in your native language, if that is quicker or more legible for you. No one will look at your notes, so you won’t be judged negatively for this.

- Practice writing quickly. I have lots of students who tell me that they can’t read their own handwriting. It’s worth making some effort to improve your handwriting. I am a big believer in italic handwriting.

- Use abbreviations, arrows, mathematical signs (like equal or plus signs), and lines to more quickly clarify information.

- Listen for “themes” of the lecture and organize your notes accordingly. For example, if the professor is going to describe two types of something, divide your paper in half with a line. If you’re going to hear about a process, use arrows or numbers to connect each step.

Here are two sample pages of notes that I took for three lectures (biology, business, and music history) from TPO (TOEFL Practice Online) 12.

Some Final Words

When teachers teach listening skills in the classroom, they often use “pre-listening” activities to give the students some context and stimulate some thoughts about the topic before they listen. Unfortunately, this isn’t going to happen on TOEFL … you won’t have any idea what the subject is until the lecture or conversation begins.

To provide that all-important context, I think a strong academic background in a variety of subjects gives you a big advantage. I found that my limited but basic prior knowledge of different subjects really helped me. For example, in the biology lecture on DNA, I had just encountered the word telomere from watching a Great Courses lecture series on the mind-body connection. The history of the opera made more sense to me because I already knew what an aria was and understood the general pattern in European history of culture moving from religious (church) settings to a more secular context. Although you won’t know what subjects you’ll encounter in the TOEFL lectures, the more widely you read and the greater variety of listening resources you use, the better prepared you’ll be to understand at least some of the references in what you hear.

Finally, remember that listening skills will help you not just in the Listening section but also in the four integrated Speaking tasks and the integrated Writing task. Your scores on those parts of the test are going to depend heavily on your ability to understand what you hear. Therefore, when it comes to studying English, you should definitely be all ears!

For more resources on improving your listening skills, see this article.

I’ve got your number

Numbers are one of the first things we learn in a foreign language, maybe because they play such an important role in our everyday life. And, for the same reason, there are lots of phrases with numbers that can be very useful in understanding and expressing yourself in English.

1 to 10. This is the most common way to rank various things in English. Maybe it’s the same in your country? With this scale, 1 is usually the worst and 10 the best. For example, every time my family went on vacation, I would ask my kids to rate the trip from 1 to 10, with 1 being a complete disaster (fortunately that never happened) and 10 being absolutely wonderful in every respect.

Perfect 10. I think this expression originated from the Olympic games, where some athletes such as gymnasts and ice skaters perform routines for which 10 would be a perfect score. In this case, though, it relates to people using a scale of 1 – 10 to rank other people in terms of their attractiveness. So, in the movie 10, the plot revolves around a man who falls in love with a woman he considers a perfect 10.

A dozen. Although industry and science employ the metric system in the US, most citizens are more familiar with the imperial system, which often uses 12 instead of 10 as a base (for example, there are 12 inches in a foot). Maybe for this reason, we often find items like eggs packaged in groups of 12 … that’s a dozen. A half-dozen would be six.

A baker’s dozen. Thirteen or 12 + 1. This comes from the idea that a baker might, as a sign of good will, throw in an extra donut or cookie with your order if you asked for a dozen.

Six of/to one, half a dozen of/to another (the other). This expression, which can be stated various ways, is a little weird, but it basically means “it’s all one and the same.” If you’ve paid attention, you will remember that six equals half a dozen. So maybe someone will ask you, “Do you want to eat at McDonald’s or KFC?” and you’ll answer, “It’s six to one, half a dozen to the other,” which just means that you don’t care and it’s all the same to you … one choice is six and the other choice is half a dozen.

Zero. This can be used as a noun to mean something or someone that is a nothing, a nonentity, or a complete failure. For example, “This day has been a complete zero. I haven’t accomplished anything.” Or, as my former supervisor used to say if a student didn’t like me, “To some folks, you’re a hero and to others, you’re a zero.”

50/50. Lots of times we use probabilities or percentages to express our ideas. If you are 50/50 about something, that means you aren’t sure what you think. Someone might say, “I’m 100% in favor of going out to the movies,” and you might say, “I dunno. I’m 50/50. I’d like to go, but it’s raining and it might be more fun to stay home and watch Netflix.”

The odds are … In the same way, we often refer to betting expressions. This would mean the same as saying, “the chances are …” For example, “the odds are in his favor for getting that new job.” On the other hand, if the odds are nil, his chances are zero.

One in a … This is a common expression to talk about something or someone that’s quite rare or very special. The higher the number, the more special or unusual the thing is, so the most common expression is probably “one in a million.”

Zillion, gazillion. In English, real very big numbers include million, billion, and trillion. But we often use the fictional, made-up numbers zillion or gazillion to describe a very large number of things. For example, I have a zillion things to do before we go on vacation. Or, I’ve already told you a gazillion times that I don’t want to give a speech in public.

Umpteen. Like zillion and gazillion, umpteen is a made-up number that is often used humorously to describe how many times something has to be or has been done. Unlike the real numbers thirteen through nineteen, umpteen describes some number larger than all of them. For example, he reassured her for the umpteenth time that she didn’t look fat in that dress. Or, he told me umpteen times how to fix my computer problem but I still didn’t understand.

I’ve got your number. A common idiom in English, this means that you’ve figured someone out and they can’t fool you. We might also say, “I’ve got my eye on you,” or “I know what you’re up to.” You’ve seen through this person’s tricks and strategies and you have figured out their real intention.

100, 90/10, 50/50 … three ways to give your opinion

In an earlier post, I talked about some strategies to use when asked for your opinion, especially in a test like TOEFL or IELTS. I’d like to elaborate on this topic, with many thanks to my long-time student Sam who spent a lot of time discussing these ideas with me.

Let’s say you’re given the following question:

Some people prefer to watch movies or films at a cinema or movie theatre. Others prefer to watch them at home. Which do you prefer and why?

So now what do you do?

First of all, many students ask me how they can generate ideas, especially when they have a very short time to prepare an answer. My most important piece of advice is to answer truthfully. If you say what you really think, all those ideas will be in your head already. And your response will sound more real, more genuine, and more personal … it won’t sound like everyone else’s.

Once you have some ideas, how do you present them? There are three different strategies you can choose.

The 100% Method

With this method, you choose one side and all the content in your answer supports that choice. Many people think you need two reasons in a 45-second response, but this simply isn’t true. You can provide one good, well-developed reason or multiple reasons … whatever comes into your mind that you’re able to talk about. A 100% answer might sound like this:

Well, I think I’d rather watch movies at home because I’m a parent of small children and we don’t have a lot of extra money for a babysitter. So a couple of nights a week, my husband and I will make sure that the kids get to bed on time and then we’ll curl up on the couch and watch a movie on Netflix. We can pop some popcorn and relax and if one of the kids wakes up we can pause the movie and take care of the situation and then go back to the movie. And if we get really tired, we can stop the movie and just finish it the next evening.

The 100% Method is also frequently used when answering an essay question such as the TOEFL independent writing task. Most test-takers choose one option or the other and then focus on three reasons (one per paragraph) supporting that choice. But as you’ll see below, although this is the most common method, it’s not the only way to write this kind of essay; and you’ll probably impress your rater if you opt for another method that’s not quite so typical.

The 90/10 Method

With the 90/10 Method, you spend 90% of your time talking about the option that you choose, but you also acknowledge the other choice. This is a good method to use if there are certain reasons or circumstances when you might prefer the other option, but you don’t want to spend too much time talking about them. A 90/10 answer could go as follows:

You know, on special occasions when I’m going out with my whole family, it’s fun to watch a movie in the movie theatre. But most of the time, I watch movies at home. It’s just easier and more relaxing. I don’t have to pay a lot of money on tickets and parking, and I don’t have to spend time travelling to the movie theatre … because where I live, the nearest movie theatre is 10 miles away. And I have more choices, because at our movie theatre, they only play one movie each week, and maybe it’s not a movie I’m interested in. If I stream a movie on my computer, I can watch pretty much anything I want.

You can also use this same method if you decide to spend most of your time talking about the option you wouldn’t choose (and this is a perfectly acceptable way to answer this type of question). So, for example:

I don’t mind watching movies at home, but I really never go to the movie theatre. Actually, I haven’t gone to a movie at the movie theatre for years. It seems like if I go during the daytime, I always get a headache when I come back out of the dark theatre into the daylight. And movies at night definitely don’t work for me because I go to bed really early. I guess I also spend a lot of time worrying about whether the tickets will be sold out and then, when I’m seated, if someone is going to sit in front of me and block my view. I just find going to the theatre kind of stressful and unpleasant, I guess.

One thing to note is that the 90/10 Method is often used when we’re writing a persuasive or argumentative or opinion essay (as is often the case in TOEFL or IELTS). This type of writing is usually more convincing (and therefore “better”) when we present an opposing argument and then proceed to counter it with our own opinion. Each paragraph will always focus on your own beliefs, but you’ll acknowledge the “other side.” For example, an essay for the TOEFL independent writing task might be organized as follows:

Opening Paragraph Thesis Statement: Although there are reasons why people might like movies in the movie theatre, I prefer to watch them at home.

Body Paragraph 1: Sometimes discount tickets are available, but movies at home are usually cheaper. The paragraph then elaborates on the savings you get (not paying for tickets, parking, transportation, babysitting, food when watching the movie, etc.)

Body Paragraph 2: On special occasions it’s fun to go to the theatre, but it’s a lot more convenient for me to watch movies at home. You then cite several conveniences (can be a last-minute decision, more comfortable surroundings, no travel to and from theatre).

Body Paragraph 3: If you live in a big city you might be able to see a wide variety of movies, but I don’t have that option where I live. You describe how your movie theatre selections are limited while you have tons of options (use some specific examples) at home.

The 50/50 Method

With this method, you spend half your time talking about one option and half the time talking about the other. You can also call this the “it depends” method.

To ensure coherence and focus in your answer (especially if you have a very limited time), it’s essential to center your response around ONE factor only. What does your choice depend on? Make that clear in your answer. Here’s an example:

Well, whether I watch a movie at home or in a theatre really depends on whether it’s a weekday or weekend. When I have to go to work the next day, I can’t stay out too late and I also don’t have enough time to travel to and from the movie theatre. So on a weekday, my wife and I really like to put the kids to bed early and snuggle up on the couch to watch Netflix. On the other hand, on a Friday or Saturday night, we’ll get a babysitter and have a special date night. One of our favorite things to do is to have dinner and then go see a film.

This method is equally effective in a written essay, as long as you organize your answer carefully in the beginning and make sure you follow the right structure. To expand, just think of more factors that your choice depends on. For example:

Opening Paragraph Thesis Statement: Whether I watch a movie at home or in the movie theatre depends on several factors.

Body Paragraph 1: Time of the week. Weekdays I stay at home. Weekends I go to the theatre.

Body Paragraph 2: Type of movie. I like to watch romantic and/or sad movies at home (embarrassing to watch love scenes with strangers, I cry easily). I like to watch action movies in the theatre (special effects, surround sound, sharing the audience’s excitement).

Body Paragraph 3: Who I’m with. When I’m alone, I watch movies at home (I don’t like to go out by myself, feel uncomfortable being by myself in a theatre). When I’m with my parents or friends, we go to the theatre.

Another important way to make your writing more coherent is to always address the options in the same order. Notice that above I talked about watching movies at home, and then at the movie theatre. This prevents your audience from becoming confused.

So which method is the best?

That totally depends on your own ideas! In TOEFL or IELTS you won’t have much time to organize your ideas, especially in the speaking section (you can afford to take a little longer with your writing). There is no right answer; there’s only your answer. In the brief period you have to generate ideas, decide quickly which is the best method to answer the question. Talk about what’s true for you, develop your answer coherently no matter which method you choose, and just pretend you’re talking to a friend rather than a stranger or a microphone.

The open window … or how to be polite in English

When I was working on my graduate degree in teaching ESL, one of my favorite subjects was pragmatics. According to my linguistics book, one of those rare textbooks that is both fascinating and fun to read, pragmatics concerns “how speaker intention and hearer interpretation affect meaning.” In other words, there’s often a hidden meaning behind what we say (or don’t say) that may be picked up, missed, or misinterpreted by our listener. Many times we say exactly what we mean (with what linguists call a direct speech act); however, when we use indirect (or sometimes no) speech, we are still communicating.

Picture this scene. You are sitting in your apartment with your roommate watching TV. Suddenly, without saying anything, he gets up and opens the window. It’s cold outside and pretty soon the room is too cold for you. Your roommate doesn’t seem to notice.

What do you think about this?

I think most people would say that this is fairly rude of your roommate. He opened the window without consulting you about the temperature of the room. So what kind of indirect speech acts could your roommate have made before opening the window?

What if before opening the window he said:

This room is too hot!

I’m hot!

You would probably think this is still pretty rude. Your roommate stated the reason for opening the window, but didn’t consult you on whether this was a good idea. The hidden meaning behind these words could be interpreted, “I’m uncomfortable and I’m going to open the window. Whether you are hot or not really isn’t important.”

What if just before opening the window he said:

It’s too hot in here … let’s open the window!

Most people would say this is only marginally less rude. Although at least he recognized you, nominally, as one of the occupants of the room, he didn’t wait for your agreement. The hidden meaning is, “I’m uncomfortable and want to open the window. I realize you’re in the room as well, but I don’t really care what you think; I want the window open.”

So how would we handle this situation more politely in English?

To make sense of this, consider the theory of Brown and Levinson, who proposed a concept of face to explain politeness. Every listener has a face … or actually, two faces. The positive face is the listener’s desire to be liked, approved, and appreciated; the negative face is the listener’s wish not to be imposed upon, inconvenienced, or bothered. Polite speech acts can appeal to the positive or negative face of the listener.

In the case of the open window, your roommate should realize that making the room colder might cause an imposition on you; maybe you don’t want it colder. Thus, he needs to appeal to your negative face using a variety of strategies, often combined together.

Indirectness

It seems so hot in here. It might feel better if the window was open.

Hedges (using words like maybe, perhaps, might, may)

I’m kind of hot. Do you think maybe we could open the window for awhile?

Questions

Would it be okay with you if I opened the window?

Pessimism (not expecting agreement)

I don’t suppose you’d like to have the window open, would you?

Minimizing the imposition

Would you mind if I open the window for a minute or two? I’ll shut it if you get cold.

Apology

I’m sorry. I don’t know why I’m so hot right now. Would you be okay if I opened the window?

Plural pronouns

Gosh, I’m getting really hot. Are you? How about if we open the window for a couple of minutes?

In general, English learners will want to focus on negative politeness because, above everything, they want to avoid being seen as rude. Positive politeness expresses friendship, support, appreciation, and solidarity … and I think if you’re a genuinely friendly person, you’ll be able to make that understood to the people you are close to. But negative politeness is important when you’re dealing with strangers, superiors, or people you don’t know well. The strategies given above, combined with the all-important please when asking for any sort of favor and excuse me when trying to get someone’s attention, should help you to handle most of these situation with aplomb.

Because saying the wrong thing or being viewed as rude or impolite can have such serious consequences, I think it’s really helpful to work with an English teacher who belongs to the culture in which you want to fit in. A good teacher can walk you through various situations and help you feel more comfortable about the right words to say to not only avoid being rude, but to make a positive impression on the people you encounter.